By Stella Lorence

BU News Service

BOSTON — Massachusetts voters may find a question about ranked choice voting, a topic which was discussed by an expert panel at a Scholars Strategy Network event at Suffolk University Tuesday, on their November ballot.

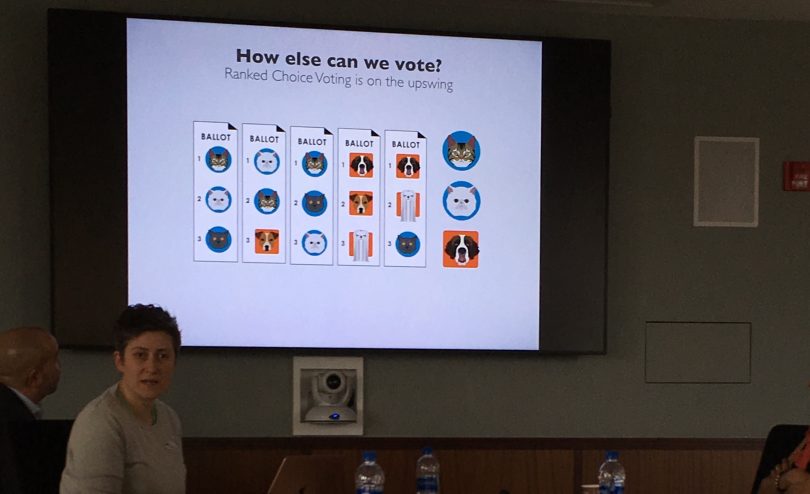

Ranked choice voting is a system in which voters rank their top candidates by preference rather than casting a single vote for one candidate. If no candidate receives a majority of first-choice votes, the results are recalculated by eliminating the candidate with the fewest first-choice votes and recounting those voters’ second choices as their first.

The RCV system was implemented statewide successfully in Maine for the 2018 elections, and it is used in some capacity in 25 states, according to Voter Choice for Massachusetts, a campaign to put a ranked choice ballot question on this year’s ballot.

“The current way we vote is flawed,” said Mac D’Alessandro, the state director for Voter Choice for Massachusetts.

The Massachusetts legislature currently faces two ranked choice propositions, according to D’Alessandro. The first is a bill that would implement RCV for all state and federal elections starting in 2022. The second is ballot language for a question about ranked choice voting on the 2020 ballot.

D’Alessandro said the ideal situation is that the legislature passes the bill and the voters will not be faced with a ballot question concerning RCV. If this is the case, D’Alessandro said Voter Choice for Massachusetts can focus time and resources on voter education rather than continued campaigning.

RCV has the potential to service better representation outcomes for minority communities without “designer line-drawing” of districts, said Moon Duchin, founder of the Metric Geography and Gerrymandering Group based in Boston.

Duchin and MGGG conducted research into what RCV would look like in Lowell, Massachusetts after the city was forced to restructure elections following a 2017 civil lawsuit from a diverse coalition of Latino and Asian-American voters.

Lowell voters were given two options for the new election structure: RCV or eight districts based on population. The voters chose districts.

“Districts are brutal for people of color in Lowell,” Duchin said. “The thing about RCV is it gives you proportionality on every axis.”

With RCV, a “geographically dispersed coalition” can still elect a candidate that speaks to their issue, Duchin said. This characteristic gives more sway to minority coalitions formed from issues that generally aren’t given as much attention, such as voters with school-aged children or voters who rent their homes.

Rob Boatright, a professor and department chair of political science at Clark University, warned against overpromising the effects that moving to RCV will have on elections.

“We’re at a very exciting moment in the U.S. right now,” Boatright said. “It also, I think, is kind of a scary thing.”

Boatright said there is inconclusive evidence that campaigns will get less expensive or competitive if there was a switch to RCV.

RCV’s effects on both campaign finance and strategy depend on candidate education as well, the panel said.

Duchin, who votes in Cambridge where RCV has been used since the 1940s, said she has had candidates knock on her door and ask for her first choice vote. She said she explains to them that they don’t need her first choice vote because of the ranked choice system, to which they reply that they don’t know how RCV works, but they still want her support.

D’Alessandro said the need for both voter and candidate education is why both the bill and the ballot question incorporate a two year “runway” period before being implemented. Should RCV pass in Massachusetts via either the bill or the ballot, the first RCV election would not be until 2022.