By Paige Albright

Boston University News Service

The wave of unease that fills an arena as fans watch an injury overcome an athlete is never a welcome feeling. So many are left wondering why, after the arguably biggest year in women’s athletics, evident inequities in injury prevention and care are being left unaddressed.

Makenna Vonderhaar, a soccer player at the University of Iowa, a D1 Big Ten program, has torn her ACL twice throughout her life playing soccer. She tore her repaired ACL about a year after her repair surgery for her first tear. She said, however, this wasn’t the case for male athletes recovering from the same injury at her power-five university.

“It’s been a little bit frustrating to see how much quicker male athletes recover compared to females,” Vonderhaar said. “I know there’s an anatomy piece in that, but, I think they just have more access to rehab resources or injury prevention. I think it’s brought awareness for me to kind of understand that there’s an issue with this.”

Injury is any athlete’s worst nightmare, as it keeps them out of play, which their income or scholarships could depend on. Any individual involved in sports is familiar with an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury or tear. This injury sidelines an athlete for a minimum of six months, requires surgery and still could leave the injured knee with less power and capabilities than prior to injury.

When torn, the ACL requires doctors to take a piece of the individual’s hamstring to re-make the torn ligament inside the knee joint. The ACL stabilizes the knee joint, which is essential in everyday life and makes participating in any high-impact sport possible.

Tearing the ACL is most prevalent in sports with heavy amounts of pivoting, quick changes in direction and contact while airborne. In the United States, the sport that sees the most ACL tears is soccer, however, this injury is seen all across the globe at every level of play.

Recently, high-profile midfielders Rodri of Manchester City and Andi Sullivan of the Washington Spirit have been sidelined for the rest of their season due to ACL injuries. Coupled with FIFA and league proposals for additional games and tournaments, many are concerned about an even greater spike in injury. The talk of athlete exhaustion and exploitation has only increased, with rumors circulating of player and team pushback against leagues.

While ACL tears in recent years have been on the rise overall, they have become disproportionately more prevalent in female athletes. Overall elite female athletes are eight times more likely to suffer an ACL injury. In soccer, a female player is 2.8 times more likely to tear her ACL than a male counterpart.

“On my team at Iowa, there’s probably been six or seven girls that have torn their ACL, and then maybe one of them has played on the field ever again. So it kind of sucks to know, once you get injured, it’s kind of like a snowball effect. Once you get surgery one time, it’s just kind of like a never-ending cycle,” said Vonderhaar. “But there’s a kid [Iowa football player] who tore his ACL in December and was playing in August, so he made it back in like, eight months.”

Looking back to the last Women’s World Cup in 2023, many teams were left scrambling as key players, such as Australia’s Sam Kerr and Germany’s Lena Oberdorf, were sidelined with ACL injuries. Just a year earlier, of the 20 nominees for the Ballon d’Or Féminin, the highest award for a women’s professional soccer player, 25% of those players suffered ACL tears the same year. Of 20 nominees for the men’s side of the award, none of them suffered an ACL injury.

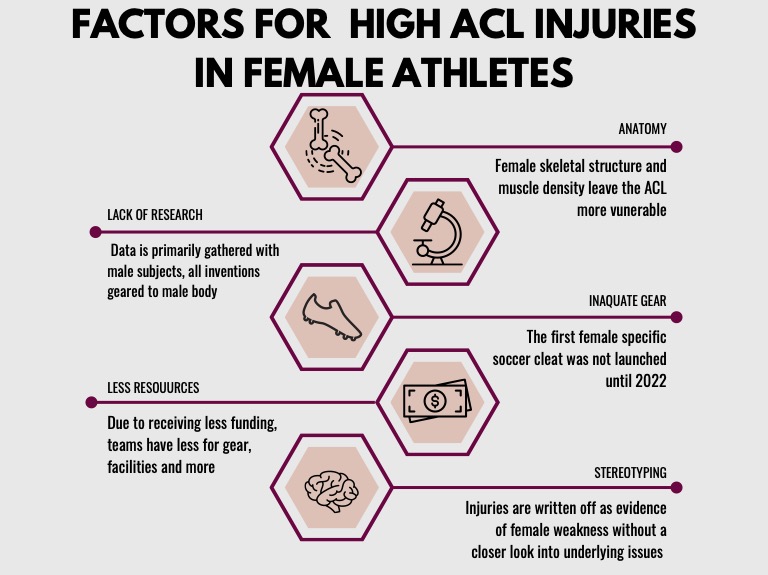

While the structure of the female muscular and skeletal systems leaves their ACL more vulnerable to injury, this alone does not account for the drastic difference in injury rate present in all levels of athletics.

At every level of play, females receive less of the media share, less funding and more. This is a long lasting effect of gender discrimination and stereotypes placing the women’s game under the men. Coinciding with these notions, on the human level of sport, women are constantly given a fraction of the support provided to men, and the rate of injuries in women’s sports is one of the major symptoms.

“I did notice there was a football player who tore his ACL at the same time as me, so I would work in the same area as him for rehab, and it was just frustrating, I did feel like, ‘am I not doing something right?’ They would get a lot more exercises and more variety of exercises, where I would do the same thing every day. I just felt like it was hard to be expected to recover the same as a male, and then, you know, not having the same to recover as quickly.”

From the first pair of shoes a female athlete puts on to the workouts meant to further their craft, female athletes are under supported. Up until a few years ago, sporting gear was made with the male anatomy in mind, then merely sized for women. The same is true for studies involving athletes or workouts designed to enhance performance.

“I just feel like I never really felt anyone was that involved in my rehab, whereas it seemed like, at least, that was not the same for the football team,” said Vonderhaar. “I would go into the football training room for rehab, and I would be a little bit shocked at all the equipment that they had that I had never seen in my entire life.”

Research on athletics has focused exclusively on male athletes, as only around 20% of studies take data from both genders and less than 9% of studies have an entirely female focus group. With females innately more vulnerable to ACL injuries, a proactive approach would be expected in protecting these athletes.

A negative feedback loop has long been the reality for female athletes. They are seen as less than compared to male athletics, so they receive less of the media share, garnering less attention leading to less revenue collected. This cycle reinforces the belief that women’s sports are less desired or entertaining than men’s sports.

However, with the success of women’s sports at both the collegiate and professional levels in recent years rivaling men’s numbers in revenue and viewership, the lights have been turned on in the club houses of teams, highlighting how female athletes are underserved in almost every way.

The amount a team spends on a single athlete on average in the NCAA is 2,000 dollars less for women than men. Even as women’s teams are returning on expenses, performing better than male counterparts, resources allocated are not equal. With less funds, lack of detailed medical research, and lack quality gear, it is no surprise female athletes see more ACL injuries.

What could be the most frustrating element to this situation is that many are quick to write off high rates of female ACL injuries to a condition of their gender, rather than confront the system that constantly underserved female athletes even after the passage of Title IX.

Vonderhaar said: “I would have never thought that there was a disparity between male and female athletes, especially at the collegiate level, because I think you would assume that everyone kind of gets equal treatment.”