By Mariya Manzhos

BU News Service

I expected Corita Kent’s exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums to serve up typical pop art from the 60’s – secular and impersonal, critiquing the commodification of culture through the manipulation of objects of daily life. However Kent’s work, infused with her background as a Catholic nun in Los Angeles, stands out among her contemporaries. By drawing on language from ad campaigns, theology and poetry, Kent articulates what a modern-day journey to God may look like: insubordinate, intellectual, stirring, joyful, exhausting and fulfilling.

“Corita Kent and the Language of Pop,” curated by Susan Dackerman, features Kent’s work from 1964 to 1969, a period in which Kent was fascinated with typography and the possible meanings of commercial slogans. It was a period defined by Kent’s openness to the outside world and exploration of pop art as a bridge between religion, politics and culture.

Although in the male-dominated pop art scene of the 60’s Kent, a nun and a woman, was an oddity, this exhibit makes the case for her as an equal to such pop art icons as Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha and Robert Indiana. With over 70 dynamic and wordy serigraphs, Kent expands the notion of what pop art is and has the potential to be.

Kent’s work invites her audience to look more closely at their surroundings and to learn to be more attentive to the layers of meanings that are hidden in plain sight. In her hands words and phrases from road signs, brands, songs and advertising jingles are transformed into a call to spirituality and social engagement.

Next to the superficial slogans, usually written in large fonts, she puts handwritten inscription from writers such as Gertrude Stein, Thomas Merton, Rainer Maria Rilke and Robert Frost. These inconspicuous additions recontextualize ads from Chevrolet and Market Basket, and endow the detached texts with abundant humanity and warmth.

For instance, in “(give the gang) the clue is in the signs” the oversized words from an ad for Canada Dry beverages “give the gang our best” urge us to give the best part of ourselves to others. To the right side, a brown strip contains words of Daniel Berrigan, Catholic priest and peace activist, penned in small writing: “the clue is in the ‘signs’ which reveal themselves to the listening heart, and so reprove our unmortified tamperings…”

Kent subtly reproaches those who take reason as the ultimate means to knowledge and certainty. Chopped up phrases gain complexity and become testimonies of human experience. In the same way, Pepsi Cola’s motto “Come Alive” serves as a wake-up call to the spirit, 7-UP evolves into a Eucharist metaphor, and Wonder bread packaging tells the narrative of the sacraments and a united community. Kent’s prints are like thoughtful prayers, encoded within a playful critique of commodity culture and consumerism.

Kent’s art emerged in response to the changing world around her. She was inspired by the efforts of the Vatican Council II in 1962 to modernize Catholic liturgy by incorporating vernacular language in the church. Kent’s ideas about reforming the antiquated traditions of the Catholic Church were deemed sacrilegious by Catholic authorities.

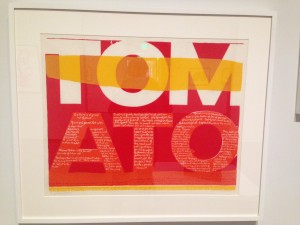

Her provocative print “juiciest tomato of all” is a homage to her audacious spirit and imagination. In red, orange and yellow she spells out the word “TOMATO” and inscribes within the wide letters: “Mary Mother is the juiciest tomato of them all.” Borrowing the Del Monte tomato sauce slogan, she humanizes the Virgin Mary, almost putting her to work in the kitchen. In such an extreme re-interpretation, Kent challenges the entire concept of the divine: what if the sacred is not in the distant and mysterious heaven, but in the mundane and the boring?

“the juiciest tomato of all, 1964” by Corita Kent at the Harvard Museums of Art. Photo by Mariya Manzhos.

In that and other pieces, Kent can be heavy-handed in her connections and efforts to bring divine messages to the people. In “Mary does laugh” she speculates whether Virgin Mary would do her grocery shopping at local store Market Basket, comparing grocery shopping to a religious experience. These excessive metaphors testify of Kent’s creative risks for the sake of art and allow Kent to come forth first as a pop artist, and then as a nun and a social activist.

In the gallery Kent’s voice echoes from a flat screen, playing a film about her teaching career at Immaculate Heart of Mary College. “We have no art. We do everything as well as we can,” she says to her students in a measured and methodical manner. This belief in the artistry of everything is at the core of Kent’s ecumenical approach towards theological, political and commercial themes. She gives equal honor to the words from Walt Whitman and cereal boxes. In the eyes of an engaged and discerning viewer they both have potential to become art.

The journey through Kent’s prints can be overwhelming. Her incessant search for meaning through words and texts left me hungering for more traditional images of objects and people. I was grateful for the curatorial decision to dilute Kent’s collection with Warhol’s JFK close-ups and Chicken Noodle Soup, Albers’s nesting squares, and Lichtenstein “Sandwich and Soda.” It was a welcome break from the straining work of deciphering Kent’s meshed up messages. Kent’s prints make us work. But often it is difficult art that is the most fulfilling. The more you study Kent’s prints, the more they invigorate your senses and intellect.

In 1968 Kent left Immaculate Heart College and the Catholic Church after decades as a nun and a teacher. This shift is strikingly noticeable as the exhibition progresses towards the end of the 60’s. In this period Kent turned to magazine and newspaper covers (many from Newsweek and Life) to convey her opposition to the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and other turbulent issues of the era. She continued to do what she’d always done – imparting another layer of meaning to the familiar contexts and expressing her left-wing stance on political and social movements of the time. Only her focus shifted from inwardly directed quest for goodness to more outward awareness of our personal stewardship over the problems in the world.

For example, in “love your brother” she commemorates King’s legacy. Grainy photos of King looking out of the window of a police car after his arrest and the Kings hugging are filtered with green and purple. On top of the images she handwrites: “The King is dead. Love your brother.” This nostalgic meditation suggests Kent’s emotional and personal connection to the past and presents Kent as a pop art chronicler, who captured the zeitgeist of her time.

Despite the seriousness layered in Kent’s work, it remains playfully irreverent, and that is why it never comes off as didactic. She intended to invent a new way to preach, but the light-hearted, colorful arrangements in Kent’s prints communicate her messages without condescension and self-righteousness. Occasionally the letters are overturned and float freely, obtaining a life of their own. Phrases are often lopsided and layered over other words, compromising legibility of the text. These flirtatious compositions are juxtaposed with the seriousness of the art’s altruistic or spiritual take-away. Yet, as I took my last glance at Kent’s lively texts and colors, it’s as if Kent was reminding me keep a light heart.

The words of Philip Roth and Simon Garfunkel written along bright coral stylized title “LIFE” embody Kent’s hopefulness: “Life is a complicated business fraught with mystery and some sunshine. Life, I love you all is groovy.” Kent manages to retain a sense of optimism, suggesting that the path to God and to our better selves can, despite the inevitable struggles of existence, remain joyful.

Chicken Noodle Soup is truly one of my cousin’s desired cuisines. I am going to ought to try this one out. It looks excellent for a cold day!