By Lauren Richards, Dan Treacy, Nicole Galioto, Joe Pohoryles and Mads Williams

Boston University News Service

During its onset, Dr. Thalia Krakower anxiously tracked COVID-19 through the news cycle. An internal medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, Krakower knew the virus would inevitably spread to the U.S. When it did, it left her grappling with the constant and ever-evolving question of how best to protect her kids.

“My husband and I are both physicians, [so] we actually pulled our kids out of school a few days before they closed schools,” Krakower, a mother of three, said. “We didn’t know how deadly [COVID-19] would be in kids, but we certainly knew that there was going to be a public health impact of having kids in school together.”

By March 2020, Cambridge Public Schools, where two of Krakower’s children are enrolled, announced schools would be closed until at least March 27. The announcement came from then-superintendent Kenneth Salim, who had already begun working remotely after someone in his child’s school community tested positive for COVID-19, according to Cambridge Day.

Out of her three children, two were attending school—one in kindergarten and the other in second grade. Krakower said that initially, it was like a “snow day phenomenon” for her kids, but that novelty quickly fell apart.

“I don’t think either of them could quite make sense of the fact that they had these teachers and friends, [that] just suddenly got taken away [with] no opportunity to ever come together,” Krakower said. “That was a really sad realization. They sort of noticed, ‘wait a minute, I’m not going to get to say goodbye.’”

Cambridge, like most cities across the country, moved to an online school model for the rest of the semester. Krakower said that as her family pivoted to digital learning, she had to deal with “endless challenges.”

“Online learning only works when you have a one-to-one parent or caregiver-to-child ratio in the house to shepherd things along,” Krakower said. “There’s a fallacy that the kids, when they’re in online school, are actually in school. They’re not. They’re at home and they need things, and the teacher cannot help them across the computer. They may be able to talk to them, but they can’t physically show them and they can’t see what they’re doing.”

A nationwide study published earlier this year by EdWeek Research Center, a research team dedicated to studying K-12 education, found that 93% of high school teachers said their students were experiencing more problems in school in January 2021 than they were in January 2020. Additionally, 72% of high school students said they were having more difficulty in school over the same period.

“Remote learning has introduced a whole new set of circumstances,” Sterling Lloyd, assistant director of the EdWeek Research Center, said. “I do think it’s harder for teachers to communicate with students and to really get a feel for where they are, how they’re feeling. It just creates barriers that weren’t there with in-person instruction.”

According to Kristin Blagg, a senior research associate studying COVID-19-related learning loss at the Urban Institute, these barriers come in many forms.

“Disruptions in terms of classes being moved from in-person to virtual learning, the restriction students may face when they’re back in the classroom, the amount they are able to interact with their peers, and then generally, the stress that’s induced during this time could have an effect on them as well,” Blagg said.

Although hybrid and remote learners experienced more difficulties than in-person learners, nearly two-thirds (64%) of in-person learners surveyed by Edweek still said they were having a more difficult time in early 2021 than in early 2020, before the pandemic.

Over the past two years, Krawkower said she noticed a change in her children’s behaviors in how they interacted with school. As online school dragged on, the excitement they once felt faded, the quality of work they turned in declined, and they were easily distracted. When the classrooms reopened, she saw mixed reactions.

“It was a difficult transition for one but a relief for the other. I think some kids couldn’t wait to get back in school, but a lot of kids had a lot of trepidation about that transition,” she said. “I know that just from talking to other parents, especially the ones that didn’t have their kids go back in October. Almost a year had gone by, and for these young kids, that was a big chunk of their life that they weren’t with other people. So it was a huge transition.”

The pandemic’s mental and emotional toll on children has long been a fear of parents and educators.

In May 2020, two months into remote education, the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education released guidance on providing support for students’ mental health. It stated in part that “the COVID-19 pandemic and its related consequences—in particular, the closing of brick and mortar schools and moving education to a remote context—is having a detrimental effect on the social and emotional wellbeing of many of our students.”

The department outlined several ways in which educators could better support students during the pandemic, with an emphasis on establishing routines, building relationships, and promoting inclusion.

On a national level, the COVID-19 pandemic has created a mental health crisis among students, including Massachusetts students who have dealt with long-term school closures and strict in-person guidelines.

Krakower said she and her husband approached explaining the pandemic to their children with caution. Their schools had emphasized safety measures, and she noticed how that instilled a degree of fear in her kids. When trying to explain the likelihood of them dying from COVID, she told them they were “more likely to be squashed by a polka-dotted elephant than die of COVID-19” to ease their worry.

“We were really mindful of their mental health,” Krakower said. “We were very careful to give them confidence and reassurance that it was safe, even though in the back of our minds, we knew it wasn’t 100% safe.”

“I personally think that that’s too much for little kids to bear, that they don’t really understand, or they shouldn’t carry that weight of the safety of the world,” she said.

Lloyd sees evidence that there should be a change in mental health resources for students going forward, even if it simply means making students more aware of resources that already exist. According to the EdWeek study, school principals generally said mental health services were offered at their respective schools while students generally said such services were not offered.

“That may reflect a reality that students aren’t aware of services that are available to them,” Lloyd said, adding that sharing these resources with students and parents, along with destigmatizing mental illness–particularly during such tumultuous times–can change that reality. “The more that young people realize everyone is going through some difficulties, the more likely they will be to ask for help.”

Krakower did not send her kids back to in-person school until February 2021. By that time, then-President-elect Joe Biden had announced plans to reach 100 million vaccines administered in his first 100 days, but Massachusetts would not announce rollout plans until March.

“Very few teachers were vaccinated at that time,” Krakower said. “It was challenging because we knew it was the right thing for them socially, emotionally, and educationally, and we were also a little bit worried about their risk of infection.”

After Governor Baker mandated fully in-person education for Fall 2021, Cambridge Public Schools were forced to reopen full time with safety measures in place.

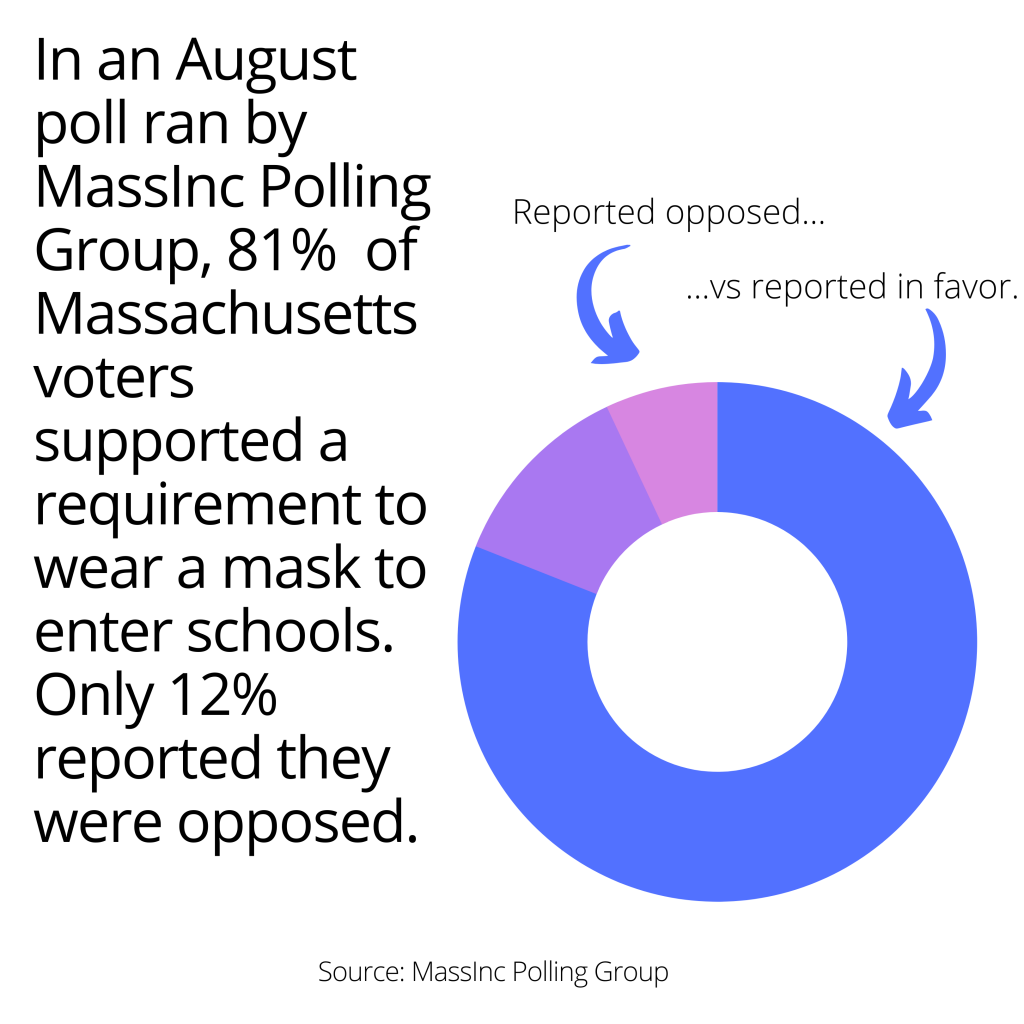

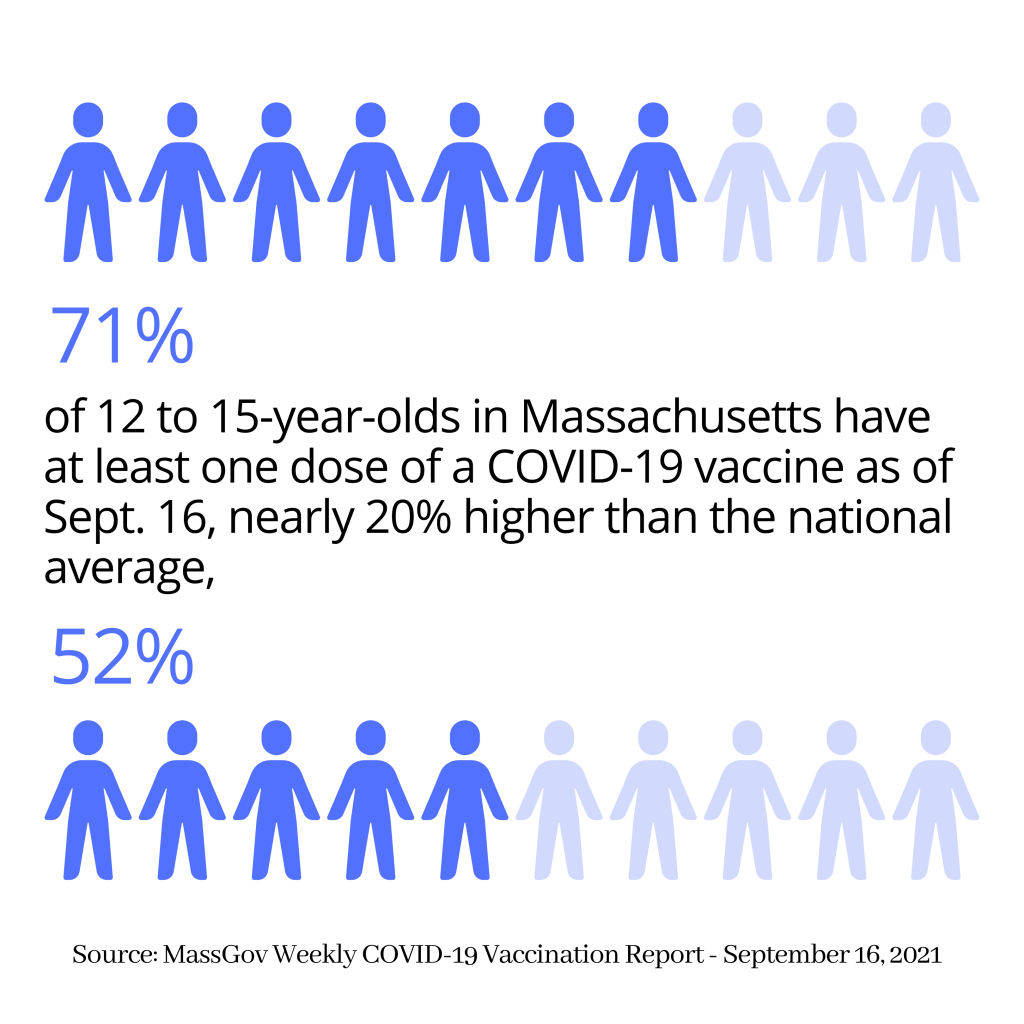

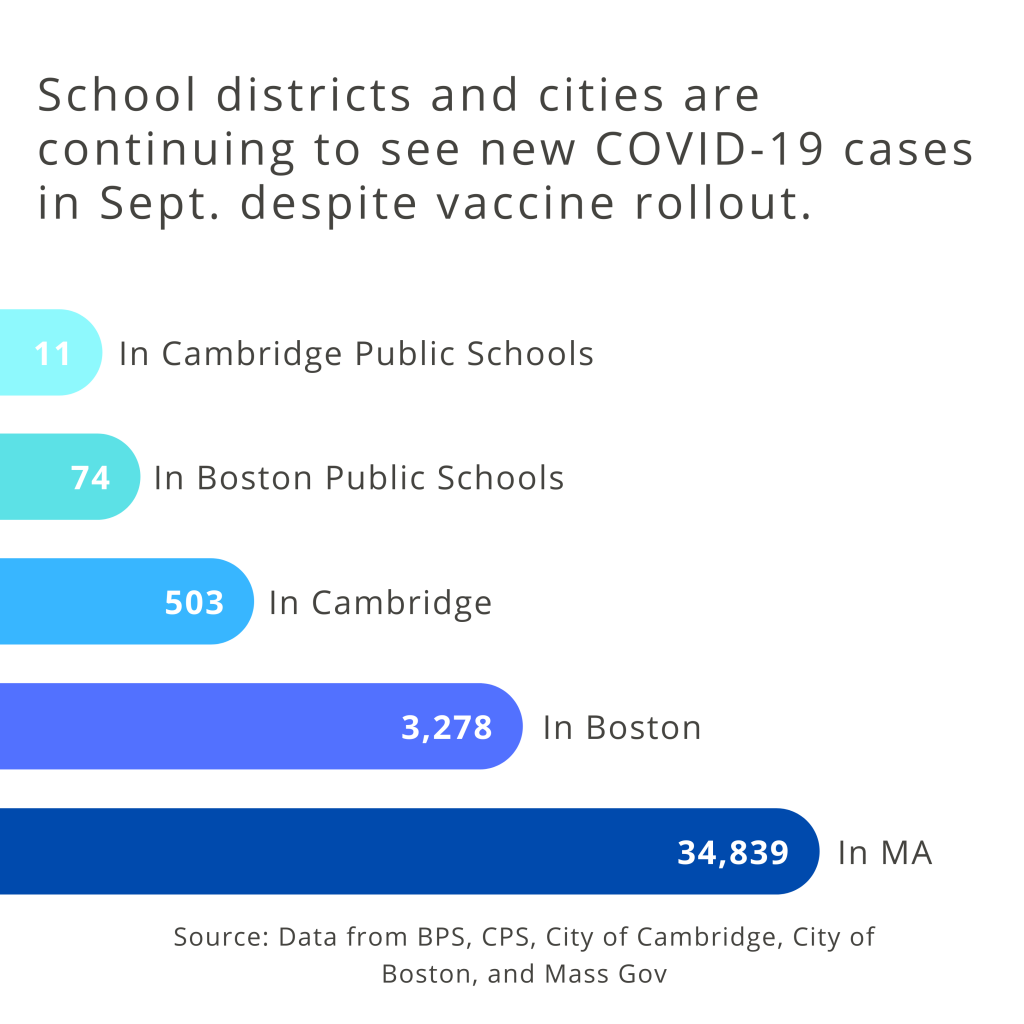

While the state’s childhood vaccination rates are higher than the national average, none of Krakower’s kids are yet eligible for the vaccine. According to Cambridge Public Schools, roughly half of their student population isn’t eligible either. Mask requirements and pool testing plans are only one part of a 22-page plan that the district has published.

Krakower said that to her, the most significant piece of the reopening plan was the requirement for teachers to be vaccinated.

“That is a huge relief for me as a parent,” said Krakower. “Although it may not be perfect with the Delta and other variants, it’s still a huge risk mitigator.”

School is more normal for students than it was at this time last year, but the long-term impact on students is still difficult to project.

“More students are returning to school this year behind grade level, which means that teachers will face challenges to teach grade-level material while also helping students catch up on missed materials from prior grades,” said Megan Kuhfeld, a senior research scientist at Northwest Evaluation Association. The organization makes academic assessments for students pre-K through 12 and is used in over 140 countries.

“Additionally, a lot of students disengaged from remote school in 2020-21, and schools were not able to reliably reach them,” Kuhfeld said. “These students will probably need additional supports to reengage with school or we could be looking at higher high school drop rates in the future.”

“These are unprecedented times, so we really don’t know the long-term effects,” Lloyd said. “I think there’s also a reason for some hope because some students are still expressing optimism that these things will get better.”

After all of the steps that Cambridge Public Schools have taken to return to normalcy, Krakower said she is cautiously optimistic.

“I get the sense that they’re building better connections this year,” said Krakower. “To be removed, essentially, from society during such formative years had a really deep impact on all of us. I think first and foremost, just seeing them excited to see other kids is my biggest goal.”

[…] source […]