By D.A. Dellechiaie

BU News Service

“I hate you” was what a shower told Esmé Weijun Wang during her first year of college. As she got older, “shadowy demons” would pursue her, but she would always narrowly dodge them. For a few months, she thought she was dead.

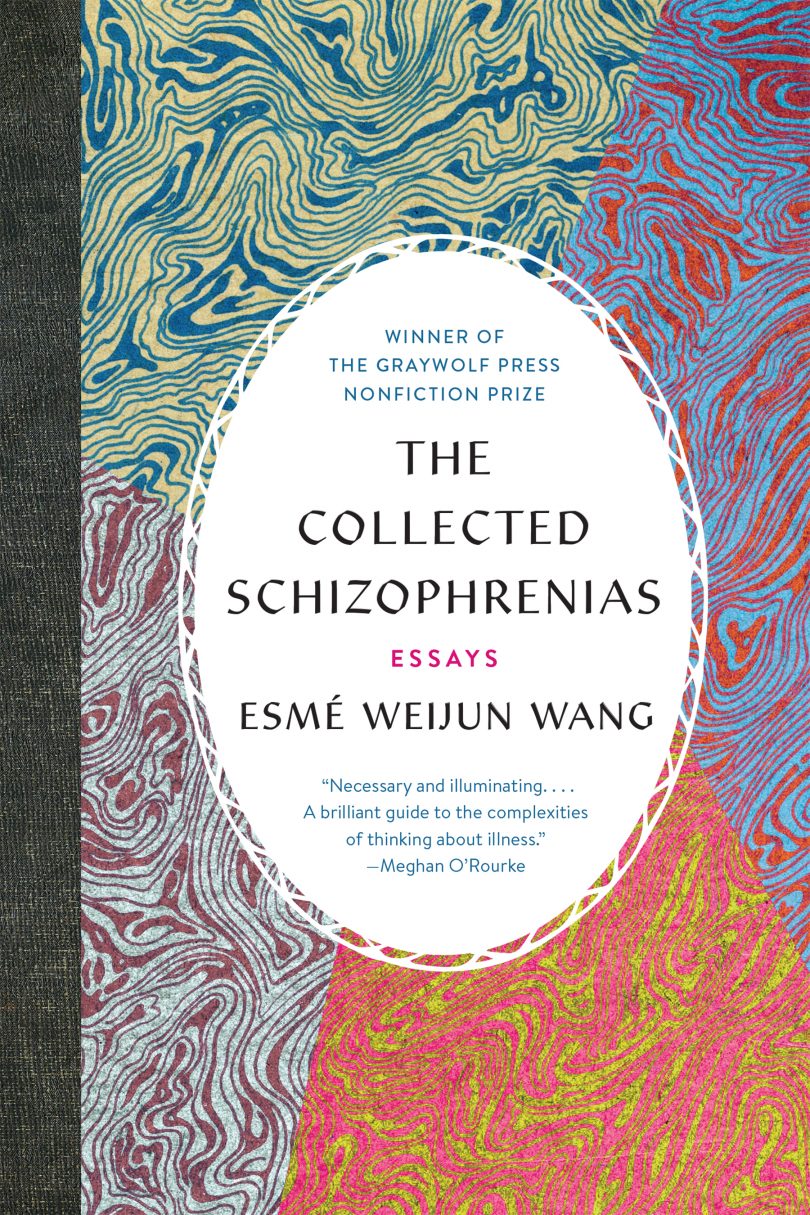

Wang’s “The Collected Schizophrenias: Essays” is a collection of essays that take an uncomfortably personal look at one of the most talked-about but rarely understood mental illnesses: schizophrenia.

Wang’s essays vary in style and content but all have her schizoaffective disorder at the heart of them. They also vary dangerously and annoyingly in readability. The early essays (“Diagnosis”, “Towards a Pathology of the Possessed” and “High Functioning”) attempt to educate readers about schizophrenia. What is so challenging to understand about schizophrenia is its actual definition, in comparison to what popular culture defines it as.

In “Diagnosis” Wang gives you a very dry and dense (and overwhelmingly boring) crash course in her illness. She even acknowledges the principal problem with the essay in the most interesting line of the whole book, “To read the DSM-5 definition of my felt experience is to be far from the horror of psychosis and an unbridled mood; it shrink wraps the bloody circumstance with objectivity until the words are colorless.” The essay then continues to descend into a series of paragraphs that read like footnotes in a scientific journal article.

“Towards a Pathology of the Possessed” and “High Functioning” are clunky essays that try to cover two aspects of schizophrenics. They discuss the burden schizophrenics put upon their family members, how some groups have tried to legalize involuntary treatment and the response from different groups, as well as how a high-functioning schizophrenic is treated and listened to. The first essay has a discussion about the movie “The Exorcist” shoved in the middle of it, which destabilizes the whole essay; the second, while about public speaking, reads like an improvised speech that drops threads and picks them back up again later when you’ve forgotten what Wang is talking about.

The later essays include “Perdition Days”, which Wang wrote while suffering from Cottard’s Delusion, a very serious condition in which the victim believes she is dead. While informative, the essay makes you feel like you just went down a WebMD rabbit hole.

This collection shines most when Wang lets us see how she interacts with people and art. In these essays (which comprise the middle section), Wang effortlessly blends memoir, arts criticism, and science together.

“Yale Will Not Save You” is about Wang’s brief time at the institution, during which she experienced her first hallucination, delusions, and her subsequent removal from Yale. While it could have fallen into pretentious tropes, the essay soars because it mixes her memories with a discussion about how colleges treat mentally ill students.

“The Choice of Children” is first and foremost an internal debate as to whether Wang wants to or even should have kids. She knows that schizoaffective disorder is genetic because her family members had it. She also worries about what will happen if she goes into psychosis while dealing with her child. These worries are wrapped around a story about how her and her husband, C., worked at a three-day summer camp for children with bipolar disorder. The connection she makes with one particularly troublesome camper creates yet more confusion in her whole way of thinking.

“The Slender Man, the Nothing, and Me” and “Reality, On-Screen” are two essays with a simple premise: Wang watches two movies and writes about them. What makes these essays different from typical movie essays is that she could have lapsed into psychosis while writing them. The first essay follows the story of two girls who tried to kill one of their friends after becoming obsessed with the Slenderman myth. Wang wonders whether she could have done something similar and realizes that she had a near-identical obsession with the movie “The Never-Ending Story” and has lost friends over it.

The second essay is about “Lucy”, a flick where Scarlett Johansson gets to use the full-functioning power of her brain, and how a person with schizoaffective disorder reacts to watching movies. What was particularly interesting about the second essay was when Wang pointed out that when ordinary people watch a movie, they have to suspend their disbelief. When schizophrenics watch a movie, it can become indistinguishable from reality. According to Wang, “the film goes forth to embellish, with vivid cinematic track, its definition of what true reality is.”

Every essay collection has a few which could have been left out. Even David Sedaris, the god of modern essay collections, has a few bad ones here and there (e.g. “Barrel Fever”). Wang is a talented writer and a genius, but her essays need a lot of editing. She will motivate her readers to learn about mental illnesses—elsewhere.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of Boston University News Service.