By: Mike Illiano and Shraddha Gupta

BU Statehouse Program

When Revere Mayor Brian Arrigo spoke out against Question 1, which would allow a Thailand-based developer to build a slots parlor in his city, his objections weren’t only about the impact it would have on Revere.

He was also concerned about what it might mean to future ballot referendums.

“This sets a dangerous precedent – it’s a bit like if a community rejected having a big box store or some other kind of development in their neighborhood, then the proponents turned around and went to the ballot statewide to try to force it through,” Arrigo said. “This isn’t the right way to go about things.”

Arrigo isn’t alone in his fears about special interests using referendums to bypass traditional legislation. As more money pours into ballot campaigns around the country, concerns are being raised about their impact.

Ballot campaigns have generated more than $50 million in spending in Massachusetts this year, well above the state’s previous high of $30.2 million in 2014. State Rep. John Hecht, D-Watertown, said Massachusetts is seeing more ballot questions partly as a result of the amount of money that can be spent on the campaigns.

“Up until the mid-1980s, there was a limit in Massachusetts law on how much money could be spent on ballot questions,” Hecht said. “Now there are no limits and these questions have been much more common.”

Getting on the Ballot

Organizations that wanted to put a question on the 2016 Massachusetts ballot had to circulate a petition and collect a total of 75,542 signatures, over two rounds. The referendum then goes on the ballot if the Legislature rejects or fails to act on the citizen proposal.

Groups looking to collect the requisite number of signatures will often hire “petition management companies” to canvas the state.

The Horse Racing Jobs and Education Committee, fronted by Eugene McCain, the developer pushing Question 1, paid $393,370 to JEF Associates for signature gathering, according to campaign finance reports.

JEF Associates also was hired to collect signatures for Question 2, which would increase the cap on charter schools in the state, and Question 4, which would legalize recreational marijuana.

Daniel Smith, a University of Florida political scientist who has studied citizens’ initiative campaigns nationwide, said petition management companies are used “almost universally” in citizens’ initiative campaigns across the country.

“This is very typical. There are very, very few initiative campaigns that rely uniformly on volunteers,” Smith said. “It’s part of the business. If you are trying to get a lawmaker’s ear in the statehouse, do you rely on volunteers to make those calls? Or do you contract lobbyists? It costs money to have advocacy, and this is another form of advocacy.”

Though collecting signatures is relatively easy through petition management companies, Smith stressed the initiative process in Massachusetts is more conservative than other states, and therefore harder to abuse.

States like California, Arizona and Oregon have direct initiative systems that allow initiatives to go straight to the ballot once the requisite signatures are collected. In direct initiative systems, questions can pass laws and rewrite the state constitution without input from legislators. Massachusetts has an indirect system – any initiative that collects enough signatures still needs the support of at least 25 percent of the Legislature before it can be placed on a ballot.

A Dangerous Precedent?

Smith said the money being spent on campaigns this year is not shocking when you compare it to money being spent in representative democracy.

“If you decry the amount of money that is spent on lobbying and campaign contributions, then you have a right to decry the amount of money spent on ballot campaigns,” he said. “But if you think that representative democracy is somehow more pure than direct democracy, then you don’t know what you’re talking about.”

The conventional wisdom that money can overwhelm the democratic process has not been the case in Massachusetts.

According to the Massachusetts Office of Campaign and Political Finance, proponents of Question 1 have spent $3.236 million. The opposition has spent $30,200. But an Oct. 27 poll by Suffolk University and the Boston Globe showed only 29 percent of respondents favored Question 1.

The same poll found the charter school ballot Question 2 locked in a dead heat despite the fact that proponents have spent $17.543 million while opponents spent $9.278 million, according to OCPF.

Josh Altic, a ballot initiative expert for Ballotpedia, a nonpartisan website for data on local, state and federal politics, said that makes Question 2 among the 10 most expensive campaigns in the country.

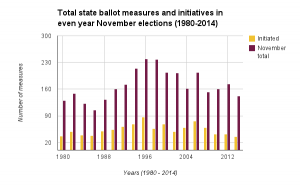

Ballotpedia lists 162 ballot measures this year in 35 states. Of those, 71 were put on the ballot by citizens’ initiatives (only 24 states allow citizens’ initiatives). There were 158 ballot questions in 2014 in 42 states; 63 were initiatives.

The purpose of citizens’ initiatives

Smith said he believes that while citizens’ initiatives are far from perfect, they act as an important check on legislatures.

“[The initiatives] shouldn’t be used all of the time. You would hope the traditional legislative process would function smoothly. But the fact of the matter is, it doesn’t always,” Smith said.

Hecht added that ballot questions are an effective way for citizens to raise issues that politicians shy away from.

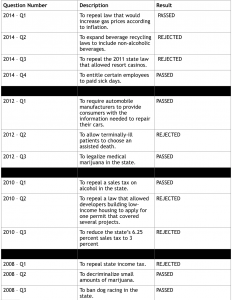

“Some of the questions being pushed are hard for legislators to handle,” Hecht said. “For instance, there is not a legislature in the country that has taken the step to legalize marijuana.”

Hecht proposed a bill based on a program in Oregon that would create a citizen panel to examine ballot questions and offer briefs on each issue. The legislation has stalled, so he has partnered with the Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University and Healthy Democracy to create pilot program examining Question 4, the legalization of marijuana. .

“The issues are often very complicated,” Hecht said. “What we hear from voters is that they find the information they currently have isn’t always as helpful as they would like.”

A pilot panel was launched this year to review Question 4. The brief produced is currently being tested with voters to evaluate its effectiveness.

“What’s missing from all of this is information from voters. The citizens’ initiative review is looking to add an additional source of information that comes from voters themselves,” Hecht said.

But other legislators remain focused on the threat that money will upend the democratic process.

“What really needs to be addressed is the money that is being poured into these referendum campaigns, more truth in advertising, public disclosure, etc. This was not the original intent of the law,” said Rep. Shawn Dooley, R-Norfolk. “And while I don’t subscribe to getting rid of the ballot initiative, I do hope we can adjust it so it reflects the purpose it was originally intended and not a tool of the few.”