By K. Sophie Will

BU News Service

BOSTON – In the wake of the horrific shootings in two Christchurch, New Zealand mosques that left 50 people dead last month, religion is on the hearts and minds of the world right now. Specifically, in a time of rising religious violence and restrictions, with religious groups opposing the social change in women’s and gay right’s circles, as well as a dramatically decreasing number of people who are religious, why would someone choose to be religiously devout?

While I do not pretend to know the pain that the Muslim community is feeling, I have been pondering how while many enthusiastically choose to be devout, being highly committed to religion in the modern Western world is unnecessarily difficult.

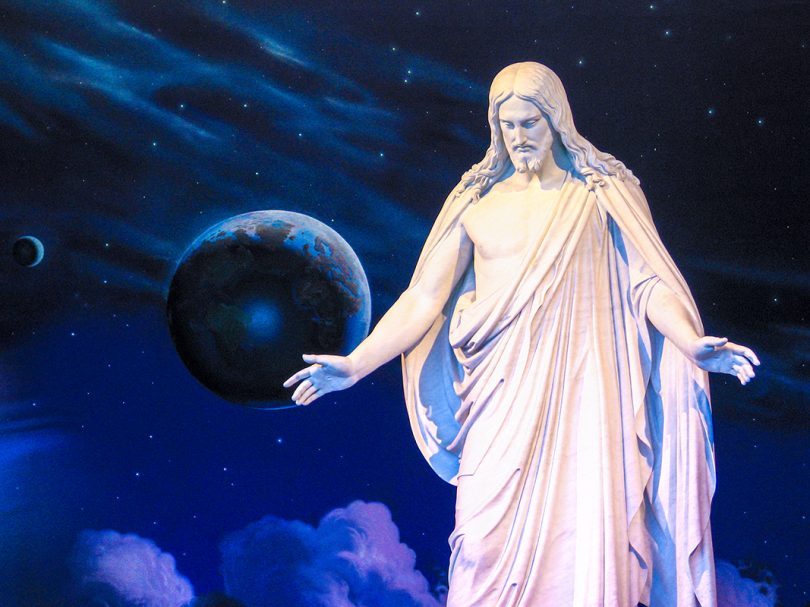

I am a Latter-day Saint, or a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and have been my whole life. My fourth-great grandparents joined the church and settled in Utah Territory – my relatives still live in the same town that bears our ancestor’s name. I am a Latter-day Saint not only because I believe in the religion whole-heartedly, but because the legacy of my ancestors is a great responsibility I carry.

Yet, while 77% of all Americans are affiliated with a religious group, only 35% of my millennial peers identify with a religion. Beyond that, those who are religious show critically low levels of religious commitment and don’t believe that religion plays an important part in their lives. According to a recent Religious Landscape Study by Pew Research Center, Massachusetts is tied for the least religious state in the country with low rankings in people who believe in God with absolute certainty and number of people who consider themselves “highly religious.”

Coming from Utah, the 11th most religious state and home of the largest percentage of people who attend religious services regularly in the country, moving to Massachusetts was a shock. I went from having access to more than 5,000 congregations and 17 temples to only 57 congregations and one temple. Additionally, in Utah, nearly 68% of the state’s population shares my faith, whereas, in Massachusetts, less than half of a percent of people are Latter-day Saints. To say I was culture shocked is an understatement.

However, the most shocking thing was how taboo it was among my peers to be devoutly religious and follow my religious customs. Among religious millennials, only 43% say they have high religious commitment. And while I personally attend religious services weekly, only 23% of Massachusettsians do.

I don’t drink alcohol because of my religion, but nearly 87% of Americans do. More specifically, it’s estimated that 60% of college students my age drank alcohol in the past month. Many social events, even events sponsored by the university, are centered around drinking, causing me to miss out on social opportunities, participate in campus life, and some friendships. Or, if I do participate in a social event, I am ostracized, laughed at, made fun of, and forced to take care of my drunken peers.

As a Latter-day Saint, I practice modesty in every season of the year. That means that at the bare minimum, I cover my shoulders and stomach, wear pants or skirts that reach my knees, and try not to wear anything too revealing. Yet, articles like “3 Ways Modesty Has Negatively Affected Our Society” circulate among my peers, saying that because I choose to dress modestly I am perpetuating rape culture and an ideal that “teaches women to be ashamed of their bodies,” even though to me, covering my body is the highest form of self-love and respect I can show.

There are so many other factors that divide the religiously devout and non-religious or even less religious, including a 10% donation from all my wages

There are even studies correlating low intelligence with high religiosity. While these are highly contested and questioned for methodological weaknesses, having the scientific community take a hit on the religious community in this way is quite a blow and highly offensive, given that most influential world leaders are religious, and even 97% of our current Congress is religious.

It shouldn’t have to be this way. It should not be this difficult to be religiously devout, because being actively religious brings me so much joy.

According to a study by the Pew Research Center, highly religious people tend to be happier. “Four-in-ten highly religious adults say they are generally “very happy,” compared with 29% of those who are less religious,” the study said. Not only that, but more than half of highly religious people visit their extended families often, compared to only 30% of their non-religious counterparts.

Most of all, being highly religious is good for society and humanity. Volunteerism and charity work among those who are religious is staggeringly higher than those who are not, with “65% of the highly religious say they donated money, time or goods to help the poor in the past week, compared with 41% of all other U.S. adults,” the aforementioned study said. Of these, 23% volunteered mainly through their church.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is known for its charity and humanitarian services. LDS Charities, the branch of the church in charge of this, have responded to worldwide emergencies and worked extensively on reducing homelessness and resettling refugees in the United States.

Also, no matter where I go, I have a community there waiting to welcome me. Because my religion is worldwide, I have over 16 million fellow members of my faith in over 30,000 congregations. By moving to Boston for college, I was never alone as my local leaders reached out to me in the first week and asked what I needed. By being religious, I have people instantly willing to help me and support me in my community. As I have traveled, this fact remains no matter where I am. That is the power of a religious group.

Yes, there are issues with modern religion. Whether that be views on homosexuality, abortion, or heaven forbid, even the horrific sexual abuse by church leaders, there are plenty of factors driving people away from religion and causing deep pain. It personally hurts to be religious when religion is causing others this pain, and it has definitely caused me to reflect on whose side I’m on – my religion or my fellow men?

I chose both. This pain will not cause me to leave my faith, but instead inspire me to change what is causing the pain.

In a brilliant TED Talk by Latter-day Saint Chelsea Shields, she describes how even though some of the traditions and customs practiced in our religion are harmful, the best way to change them is from inside the church, not outside.

“I cannot tell you the hundreds of people who have said, ‘If you don’t like religion, just leave.’ Why would you try to change it?” she said. “Because what is taught on the Sabbath leaks into our politics, our health policy, violence around the world. It leaks into education, military, fiscal decision-making. These laws get legally and culturally codified.”

In a religion that is so tight-knit, these changes and challenges to unacceptable practices are best received from practicing members. Instead of abandoning my religion for the things I don’t like about it or agree with, I am staying devout with daily increased determination to challenge the policies I find harmful.

It’s time that my devotion stopped being viewed as a weakness, and instead, great strength and a joyful part of my life that makes me, and the world, better.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of Boston University News Service.