Mood swings, depression, changes in sex drive: any woman who’s ever been at the mercy of hormonal birth control recognizes the roller coaster ride of side effects that can accompany contraception.

Not surprisingly, then, many women expressed outrage when a World Health Organization panel shut down a study of a male contraceptive method because it appeared to induce those same side effects in men. The WHO panel’s decision in 2011 ended the trial early and discourages future trials of other injectable hormonal methods for men. The study was published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism in October.

Other studies have indicated a bias in health care against taking women’s pain seriously. But birth control operates in a different context, because the biological stakes of pregnancy are different for men and women.

Men currently have just two options for reliable contraception. Vasectomy, the only long-acting method, is generally not reversible. For men who don’t want sterilization, that leaves condoms, which have a typical use failure rate of 18 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Still, many men and their partners rely on those less-than-ideal choices. According to a 2014 report from the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics, about one in seven women using contraception rely on male condoms or a sterile partner. Prior surveys have shown that a significant portion of men would be willing to use a new form of contraception, like a pill, but the development of those methods has been drawn out over decades.

“The joke in the field has been that the male contraceptive has been five years away for the last 30 years,” said John Amory, a male contraception researcher at the University of Washington.

Hormonal methods are among the most promising because researchers have studied them for a long time and understand how they work. Other methods include attempts to reduce the ability of sperm to swim or to physically block the sperm from leaving the body. Recently, for example, researchers at the California National Primate Research Center established that Vasalgel, a polymer injected into the vas derefens of 16 male monkeys, blocked sperm effectively enough to prevent pregnancy in all the females for one to two years. However, there’s a long way to go before the method can be considered safe and effective for use in humans. The study appeared in Basic Clinical Andrology in February.

The truncated study, which began in 2008, was designed to suppress sperm production with combination of testosterone and a progestogen. Researchers in 10 countries across four continents enrolled 320 men to receive the new contraceptive method, which was delivered via injection. In accordance with the WHO review panel’s recommendations, injections ceased in 2011, but the researchers continued to follow up with participants into 2012.

The two hormones tested in the study work together to shut down a signaling pathway from the pituitary gland to the testes, where the body produces both sperm and testosterone. As testosterone output from the testes falls, the creation of new sperm drops as well.

To qualify for the study, the men needed to be in a monogamous heterosexual relationship of at least a year and have a normal sperm count. Among the required relationship conditions: “coital frequency” averaging at least twice a week, no intention of breaking up, and no desire to become pregnant.

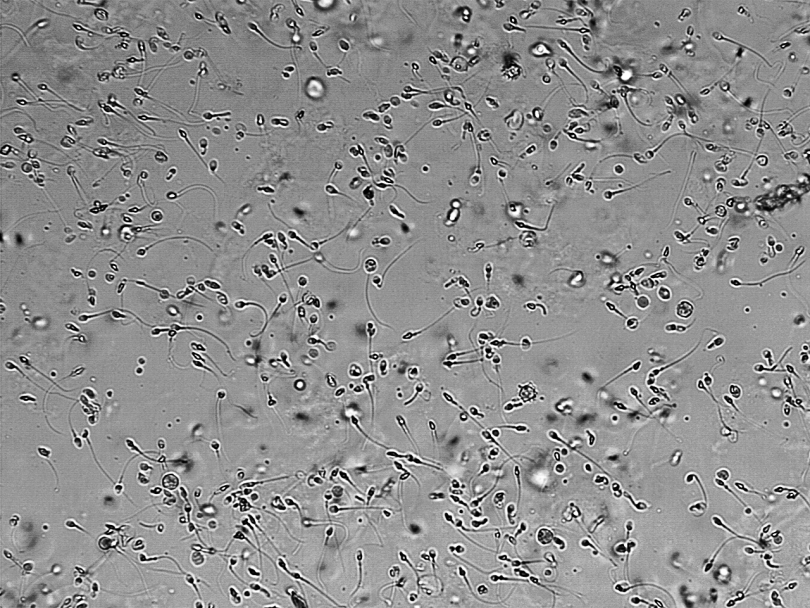

Once a couple was approved for the study, the researchers injected the male participants with the hormone combination every eight weeks. When two consecutive semen samples showed a sperm concentration of less than or equal to one million sperm per milliliter, the men could stop using additional forms of birth control. And if that still seems like a lot of sperm, consider that a normal count numbers at least 15 million sperm per milliliter.

For up to a year afterward, the men continued receiving injections every eight weeks and used no other form of contraception. After the injections stopped, the semen sampling continued, and 95 percent of the men in the study regained a normal sperm count within a year. Four couples became pregnant and some men did not experience adequate sperm suppression, resulting in a success rate of 92.5 percent— lower than vasectomy, but much better than condoms, and slightly better than the pill.

More than 75 percent of men in the study were satisfied with the regimen and would have liked to continue using it— a higher degree of satisfaction than women rate most forms of birth control. “I think that’s very positive,” said Diana Blithe, a director of contraception development for the National Institutes of Health, adding that it “goes against this idea that the men were just complaining too much.” The most common side effect was acne, but other, more serious side effects also occurred— namely mood changes, depression, increased libido and pain at the injection site. The WHO monitoring panel that reviewed the study’s progress in 2011 deemed those side effects too risky to continue the injections.

“A good chunk of [media reports] are saying that ‘men couldn’t handle … the side effects, so they all withdrew from the study,’ ” said Doug Colvard, a co-author of the study. But, he said, “that’s not the way it happened at all.” Colvard is a program director at CONRAD, a research nonprofit in Virginia that focuses on global reproductive health and partnered with the WHO to conduct the study.

He explained that the trial was designed to evaluate safety and efficacy of the given method in a large group of men, not to “be a comparative study to female hormonal methods.” Yet even such a comparison might have a twist. Because men have no chance of personally experiencing a dangerous pregnancy complication, it’s that much more challenging to justify inducing a dangerous side effect.

“There is an inherent difference,” Colvard said. “Men don’t get pregnant.”

But this unequal risk doesn’t mean that men don’t have an interest in sharing preventive responsibility. Eighty-seven percent of the male participants in the WHO study said they would like to use a form of birth control similar to the one that was tested. But pharmaceutical companies have been reluctant to back such development due to perceived slim profit margins. The first pharmaceutical company to offer male birth control will face the additional hurdle of introducing an entirely new class of medications.

It’s “more challenging than just entering the field with … an improved version of something that’s already out there,” Blithe said.

Finally, the industry could also worry about cannibalizing its own sales if it views male contraception as a direct competitor to female birth control methods. But Blithe doesn’t see it that way, and pointed to men who’d like a long-lasting but not permanent form of birth control.

“That’s a market that right now is at best using condoms,” she said. “So I would think [male birth control is] probably going to displace non-users or condom users more so than women who use female methods.”

In addition to that untapped market, she also expects that most couples will double up on their birth control methods rather than choose one over the other. “And that,” she said, “will end up in fewer unplanned pregnancies.”