By Claudia Chiappa

Boston University News Service

Anniversaries are a time of remembrance.

When lives were being changed one year ago by the initial spread of U.S. COVID-19 cases, few people realized they were living through history. Those that did, however, chose to serve future historians, documenting this unique moment in their lives through journaling.

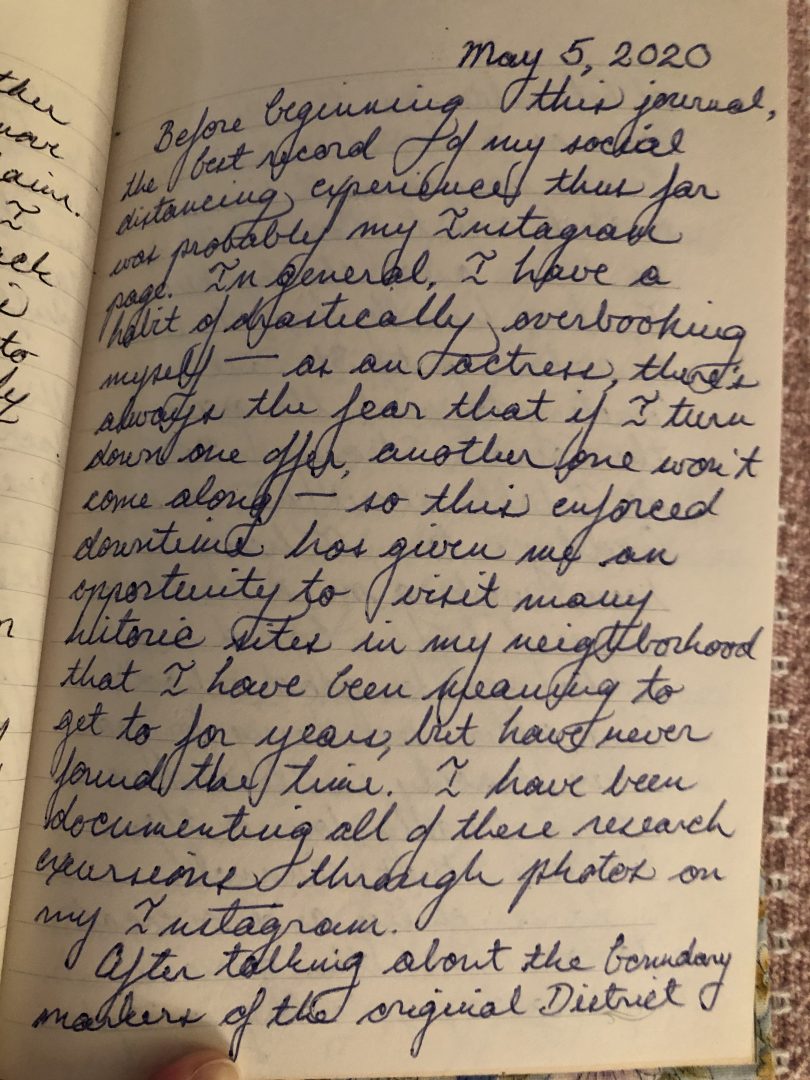

Laura Rocklyn, a graduate student at Emerson College, an actress and history enthusiast, has been journaling for most of her life. When individuals’ lives started shifting online, including her classes and theatre performances, Rocklyn realized that something monumental was happening.

Rocklyn’s writing covers everything happening during the week, from personal experiences to broader stories about world events. Rocklyn has used writing as a coping mechanism during these unprecedented times.

“Sitting down at the end of every week and writing what I am taking away from the week has been very helpful,” Rocklyn said.

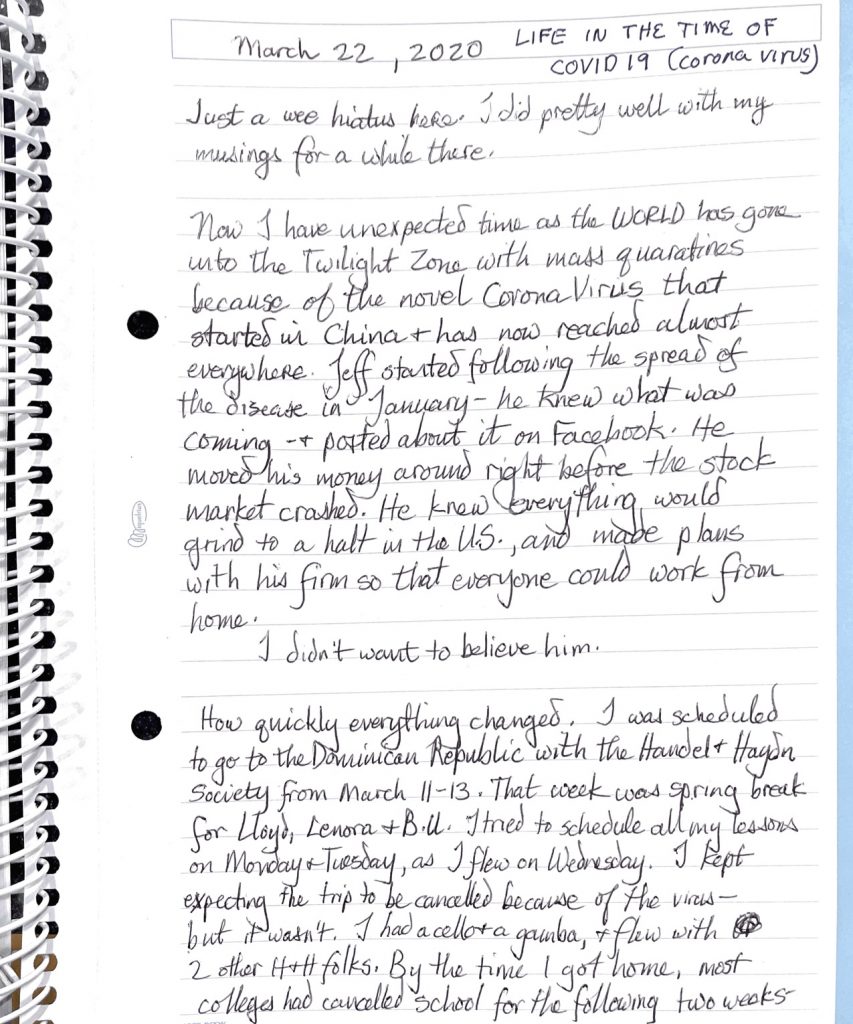

Rocklyn is not alone. Sarah Ellison, a freelance cellist and lecturer at Boston University, had always been a sporadic diary keeper until the pandemic hit. Once she realized she had more time on her hands, she decided to start journaling more regularly. This was her coping mechanism.

At least once a week, Ellison writes about everything going on in her life, including specific and mundane activities, such as wearing masks, getting tested or struggling with vaccination appointment registration.

One year later, Rocklyn and Ellison are both still writing. Their content has shifted over time, changing as the world processes new information every day. Their writing will one day be regarded as a primary source, a firsthand account of a historical moment, as both Rocklyn and Ellison plan to submit their journals to the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS). Several organizations worldwide committed to collecting testimonials about the pandemic, aware of the value they will bear in years to come.

The MHS has kept close records of this historic year. Starting in late March, MHS started posting prompts on its website, encouraging people from all over the United States to share some of their thoughts and experiences about the pandemic. Rocklyn discovered her journaling project here.

Prompts initially posted weekly and later biweekly vary from questions about the use of masks to school reopening, politics, and vaccine rollout. Contributors can post anonymously online and can choose to contribute to the collection with text or images.

“They write about their families, they write about their fears, they write about their frustrations having to deal with small children at home, or not being able to visit parents and grandparents,” Brenda M. Lawson, vice president for collections at MHS, said. “It’s a way to vent frustration.”

Since MHS started posting prompts, it has received 156 contributions from 114 individuals, according to Lawson. In addition to its online collection, MHS is planning to collect journals from people who kept diaries throughout this time — people like Rocklyn and Ellison.

Source collection is not something new to MHS. The organization has been collecting first-hand testimonies of historical events since its foundation in 1791. Its collection, which can be browsed online, includes books, maps, newspapers, manuscripts, photographs and artifacts telling the stories of several pivotal moments in history.

The COVID-19 collection gathers the experiences of dozens of people from different backgrounds. A specific section of the website allows teachers to upload their students’ writing.

“What you want is multiple perspectives, so that together, when you look at [the perspectives] across this group of people, it’s this tapestry of voices,” Ellison said.

Another online collection, “A Journal of the Plague Year,” was started by Arizona State University’s School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religion Studies. The website launched in mid-March 2020 as a history project related to the pandemic. However, it quickly expanded beyond ASU.

A Journal of the Plague Year’s archive allows people from all over the world to submit images, videos, audio interviews, social media posts and other formats. Dr. Katy Kole de Peralta, ASU professor and project lead, said the archive has nearly 14,000 stories — most of them texts and images. These contributions allow historians to have a glimpse into the everyday lives of a population during a pandemic.

“If you read a newspaper article from the 19th century, you have no idea what people thought about an article or if they even read it,” De Peralta said. “Now, we have so many ways to collect [perspectives] that allow us to filter through layers of history and their reception. It includes social media posts and comments, personal reflections on boredom, fear, humor and silver linings, pandemic-inspired art and music, the toil and labor that goes into making fabric face masks, the smell of a sourdough starter [and] the frustration of online learning. These are all perspectives that we don’t have from 100 years ago during the last pandemic.”

One year after the beginning of the first lockdown, few people can say they expected the pandemic to alter life for so long. This ongoing trauma has allowed people to adapt to the new normal. Lawson said MHS has been able to record the ups and downs throughout the pandemic.

“The archive tends to reflect the pulse of the contributors — whatever is happening out in the world gets reflected in the archive,” De Peralta of ASU said. “We’ve seen a lot more stories about vaccines. There are always stories about holidays and how gatherings [and] celebrations have changed since last year. There is a ton of pandemic fatigue. People are ready to get their kids back in school and get their lives back on track.”

While the pandemic brought despair and struggles for many, it also opened the door to a world that many had never experienced, one where suddenly time was abundant. Quarantining in their houses and unable to go outside, many found that they could suddenly enjoy life in a new way.

“At the beginning, there was a lot of despair,” Rocklyn said. “But then, a few months in, there was a turning point where people realized suddenly they had downtime for the first time in years. They could start to pursue passion projects or do other things.”

Similarly, Ellison said that over time she started noticing things to be grateful for — even in the midst of a pandemic.

“I was just much more attuned to nature,” Ellison said. “I’d take the dog for three-mile walks every day because we could walk around our pond and I had time to do it. [I also heard] the spring peepers in the evenings in March, [saw] lady slippers [and enjoyed] rare flowers you can only find in the woods in June; I have never really had time to stop and smell the flowers.”

Ellison said she found beauty in being able to appreciate what was around her in a new way. This bled into her time with family.

“We all sit down to eat dinner together every night, and that’s a time where we can catch up and talk and discuss what’s happened during the day,” Ellison said. “I can’t remember when we did that [before].”

Whether journals are filled with stories of individuals walking their dogs and reconnecting with families or plagued with more somber entries, they are assured to bear value for future historians.

“Sometimes people hesitate to contribute to the archive because they think their history isn’t noteworthy,” de Peralta said. “Capturing the ephemeral parts of life is what makes the archive unusual and special.”

However, Ellison hopes her entries show that there was more to the last year than despair. There were resilience, strength and perseverance.

“I hope [future generations] will get a sense of what life was like during the time the world stopped,” Ellison said. “I hope that by reading what I write, people in the future can get a sense of how we rode out the pandemic.”

March 2020 signaled the beginning of what has been a life-changing, unpredictable year for many people. Twenty-eight million cases and half a million deaths later, COVID-19 remains a looming presence and a steady threat.

Neither Ellison nor Rocklyn knows exactly when they will end their COVID-19 journals. Even with vaccinations being distributed and states rescinding restrictions, it is hard to pinpoint a time in the immediate future where the pandemic will be a memory. For now, they continue writing.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Sarah Ellison is a freelance pianist. She is a freelance cellist.