By Kristian Moravec

Boston University News Service

When the Osage Tribe catapulted into oil wealth in the early 1900s, a mysterious string of untimely deaths suddenly plagued the community. As the death toll mounted, an outcry rose from the community to find the killers. The investigations that ensued would unravel widespread conspiracy of rapacious white folk killing tribe members for their headrights – oil trust money assigned to Osage.

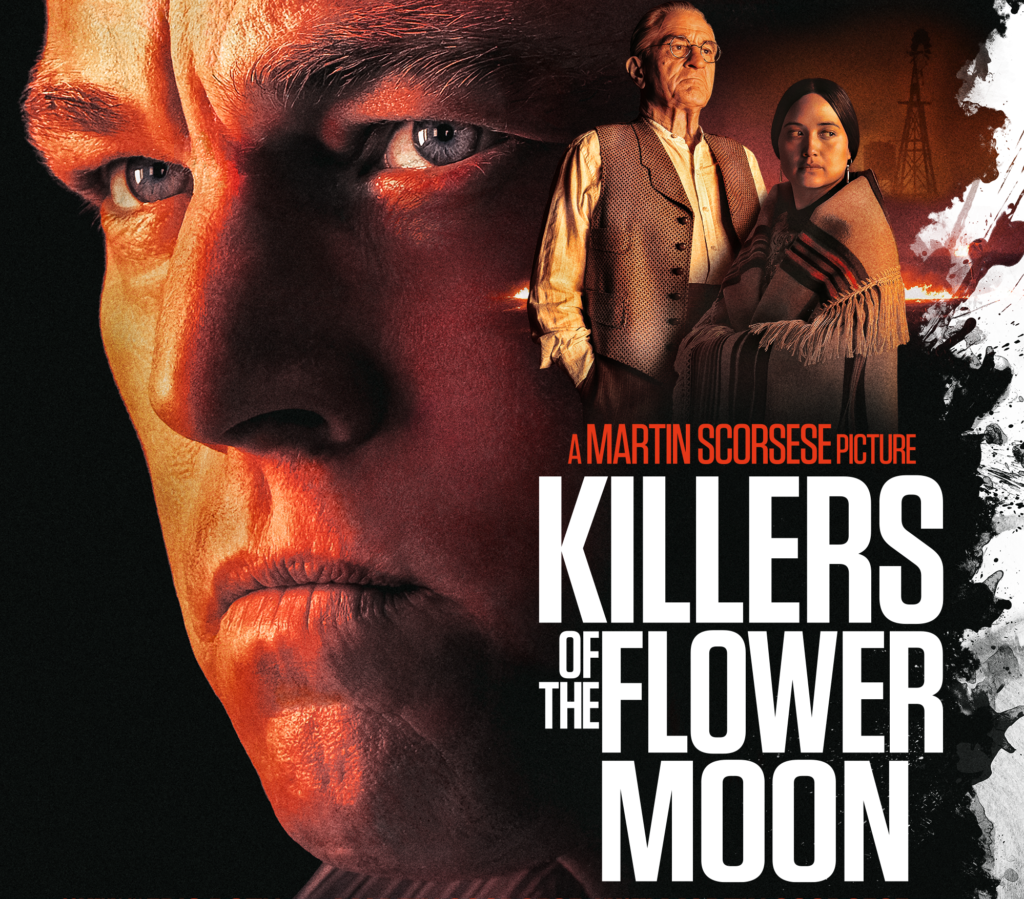

Based off David Grann’s nonfiction book, Martin Scorcese’s Killers of the Flower Moon tells the story behind the murderous conspiracy that took place in Oklahoma. The story zeros in on World War I veteran Ernest Burkhart – played by Scorcese’s longtime collaborator, Leonardo DiCaprio – who arrives in Osage County to live with his Uncle William Hale, played by Robert De Niro.

Ernest, driven by greed, is roped into his uncle’s scheme to get rich by murdering and marauding in the Osage community. In the process, he marries an Osage woman, Mollie Burkhart (played by Lily Gladstone), and Hale plots to murder members of her family to inherit their headrights.

Having read Grann’s book, which intricately documents the conspiracy that coincided with the formative years of the FBI, I was eager to see how Scorcese – a film patriarch who brought us The Departed, Shutter Island, and Wolf of Wallstreet – would portray such a thriller on the big screen.

But after sitting for 3 hours and 26 minutes of moving performances, I left the theater with mixed feelings. Between the odd pacing of the film and the dearth of historical context, I question whether Scorcese was effective in informing the masses on how sinister these killings really were.

Let’s start with what went right

As expected, the performances were Oscar-worthy. Lily Gladstone brings Mollie Burkhart’s character to life on screen with a raw, unfettered display of gut-wrenching scenes of grief and endurance despite all odds. Leonardo DiCaprio aces the greedy but bumbling nature of Ernest Burkhart. Robert De Niro shows us expert duality in how sinister even the seemingly kindest of men can be.

In a refreshing twist of expectations, Scorcese and DiCaprio decided to spare us another white savior story by decentering Grann’s original hero, Detective Tom White. Portrayed as the lone wolf cowboy with a strict code of morals, White took up a good chunk of Grann’s book, largely overshadowing Mollie and other Osage stories. White, who was played by Jesse Plemons, only took up a small portion of screen time.

Scorcese also worked closely with the Osage community in the making of the film, highlighting their culture and language in ways that Grann could not quite match in the book. Many characters in the film wore traditional Wahzhazhe (meaning water people) clothing made by Osage artists. From ornate, feathered top hats to intricately layered beaded necklaces, the audience gets a detailed look at visual staples.

Actors also frequently spoke in Osage language taught to them by Osage Nation Language Teachers of Osage culture. I would even argue that the film was immersed so deep into the culture that it lacked sufficient English subtitles. Regardless, Scorcese’s care and respect for the Osage was clear on screen.

The complicated bits

Though Scorcese corrected some of my critiques for Grann’s book by ridding the story line of white saviorism and giving us better cultural insight, he failed to pace the film in a way that kept viewers engaged for all three hours (and change). Worse yet, with all this time, he still failed to parse out the vital contextual elements so audiences could fully understand what actually happened.

To start, the beginning sequences of the film, though beautifully shot, moved too quickly. This left gaps in the background for those who might not have known about the actual events that occurred.

From these opening scenes of Osage men dancing in oil spewing from the ground, to silent film-esque edits of wealthy Osage, the pace then slams to a halt when DiCaprio appears on screen. From the introduction of Ernest and onward the film moves at a snail’s pace, only to temporarily quicken when the action happens. In fact, the most terrifying (and arguably the most important) parts of the film seemed rushed, not leaving viewers enough time to connect with the drama.

For those who haven’t read the book, Grann builds each chapter and section with cliffhangers to keep us turning pages. Clues were budgeted and strategically dispersed throughout the story to continue building suspense without revealing too much. At times, it was hard to believe I was reading a nonfiction book. It felt like a fiction “who-dunnit” novel. Because of Grann’s brilliant writing, readers can’t clearly point the finger at William Hale and Ernest Burkhart until much later in the story.

The film loses that driving element of suspense as the villains are introduced in the very beginning. This is the tradeoff Scorcese made when he decentered Detective Tom White. Instead, the only conflict that drives the film is anticipation for when Ernest gets caught.

To make matters worse, viewers are left with little reflection on exactly what happened by the end of the film. I expected some sort of epilogue as the screen faded to black. Instead of seeing summaries of what happened to Mollie, Ernest, Hale or even their descendants, the credits start rolling. As the lights began to brighten in the theater, I audibly exclaimed, “That’s it?!”

I later learned that Scorcese had attempted to offer some sort of epilogue through his seemingly random scene at a live radio show towards the end. In this scene, white performers somewhat absurdly act out the conspiracy to an audience, utilizing stereotypical Native accents and playing drums.

While this bit was great commentary on how white society dismissively consumed news of the Osage murders at the time (and perhaps a slight dig at true crime consumption today), it did not wrap up the affairs that occurred after the trial, which were quintessential in understanding the scope of injustice that transpired against the Osage.

The film should have noted that Ernest Burkhart, William Hale and other conspirators that were sent to prison for the murders were released on parole despite protests from the Osage community. Burkhart also received a full pardon for his role in the murders in 1965.

The film should have reiterated just how many people died in the end. David Grann estimates that hundreds of Osage were killed because of their headrights, and not just by William Hale and his gang, but systematically by white guardians, relatives, doctors, and so on. As Grann said in an interview with PBS, “It became a story about who didn’t do it.”

Key Takeaways

Even if the Scorcese did not execute the film in a way I personally would have liked, his emphasis on working closely with the Osage community and doing away with Tom White as the center star was an applaudable and welcome change in the mainstream film industry.

Still, the importance of telling stories of historical value like the Osage murders is to leave viewers with a sense of better understanding. Scorcese left us with more questions than answers.

For those of you who haven’t, go read Grann’s incredibly well-researched book to get the full historical context of what happened.

Yeah crappy movie. Get over it Scorsese. No lessons learned & plenty of suffering to haunt my mind for a lifetime. I constantly complain & lost faith in your talent. Move on with your lead men too. Develop new relationships.