By Pratibha Gopalakrishna

BU News Service

The warmth of the Harvard Museum of Natural History is a welcome relief from the autumn gloom. I pull the faded gold handle of the wooden door and enter a small veranda showcasing a full set of saber-toothed tiger bones on the left. My roommate and I climb a set of old iron and moss-green-painted wooden stairs to reach the third floor, where a cream-colored, gauzy, carpeted hallway greets us, gift shops flanking both sides.

After eyeballing a few items in one of the gift shops, I enter the hall labeled “Earth and Planetary Sciences.” I am greeted by a huge white, well-lit hall lined with rows of wooden cases and a few people peppered around. I warn my friend that this will take a lot of time, and I turn right to start my adventure. And to put my limited knowledge of rocks to good use.

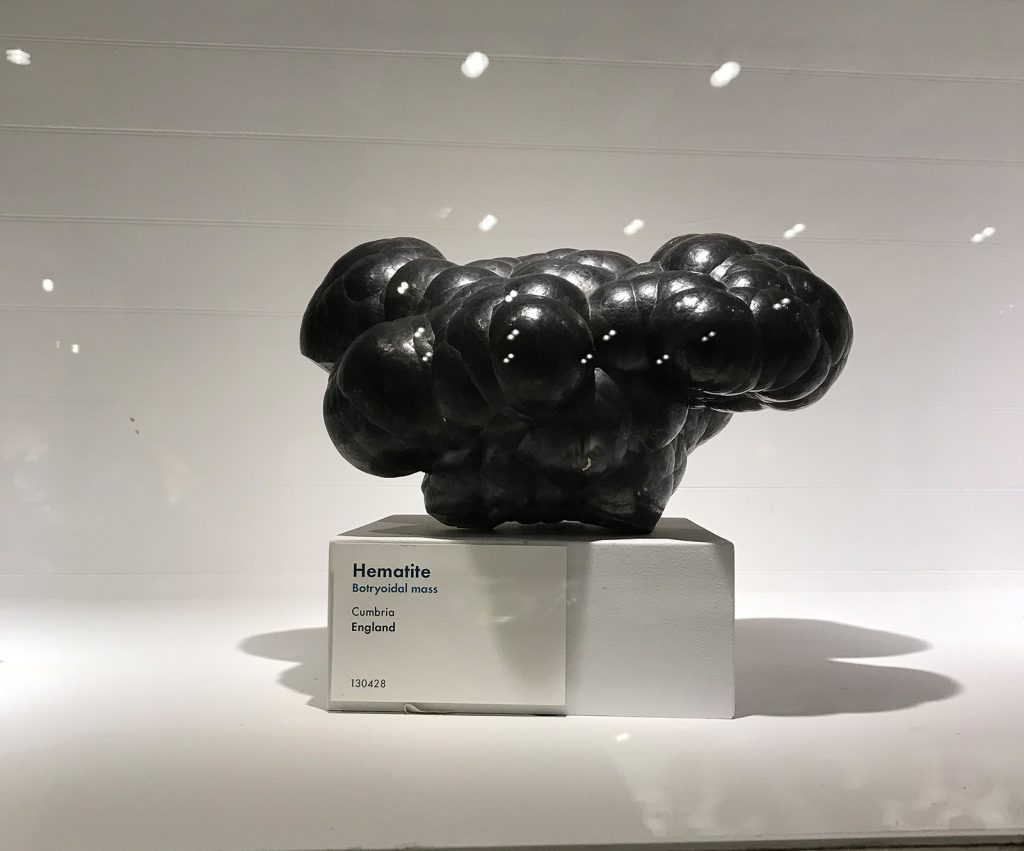

The first display I see is of hematite, a non-magnetic iron oxide which is known for its reddish streaks. But this one is entirely black, resembling a Dairy Milk Silk Bubbly chocolate bar. The name “hematite” is derived from the Greek word “haimatitis,” meaning “blood-red” because it has a red hue when powdered. Hematite is used extensively as a red pigment and is also used as a principal component for the production of steel.

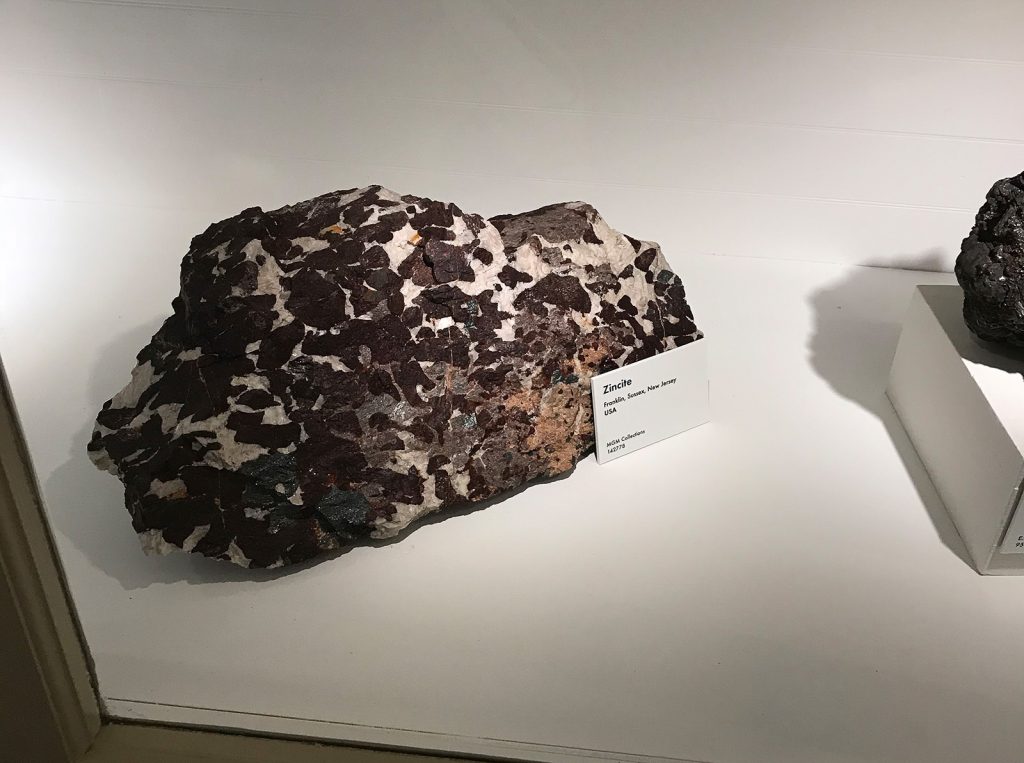

I move from display to display, and with every step, my curiosity builds, along with my weird imagination. There’s an ore that looks exactly like Professor Snape of the famous Harry Potter books, running as his black robes whirl behind him, and another reminds me of strawberry shortcake (the actual cake, not the elusive cartoon character).

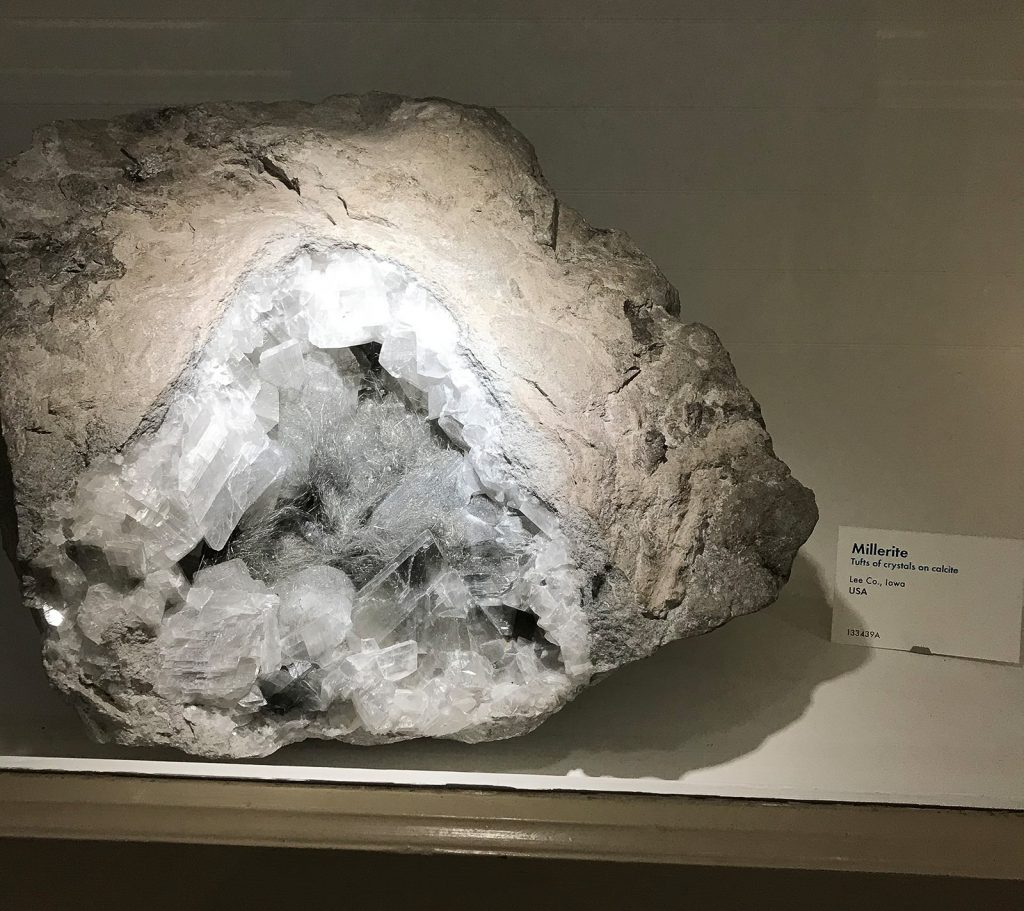

There’s an ore shaped like an old tape recorder, with a grayish-black body and golden circular discs resembling speakers. Another ore looks like it’s sprouting grayish-white hairs from its white marble depths. There’s one that resembles the moss, while another looks like a dead coral.

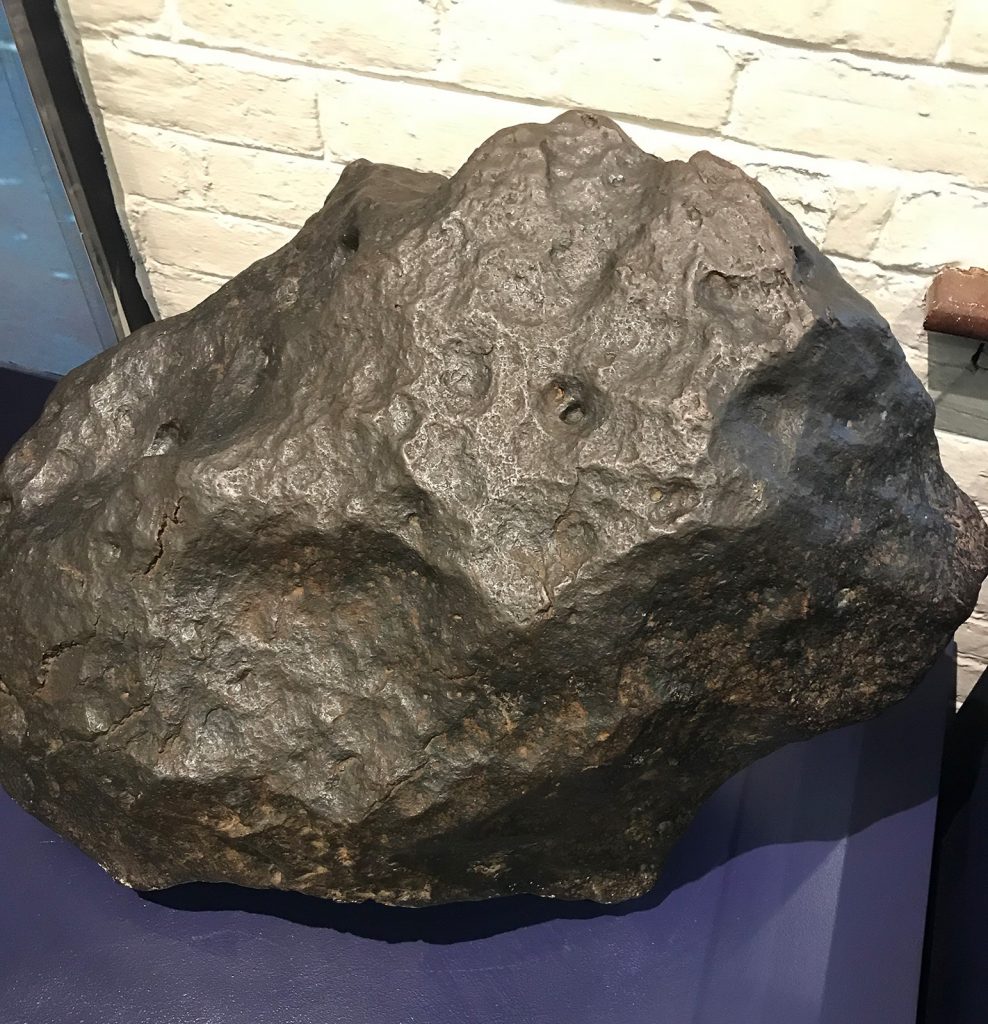

I continue on to the meteor section that is flanked against the right wall of the room. I read the general description of the section and look beside a glass case that encloses a few small meteor fragments to find a huge meteorite, sitting naked. It wears nothing but a placard that says it came by way of meteor showers that dropped over 2,000 kilograms of meteorite fragments in an area around Coahuila, Mexico.

I hesitantly touch the meteorite; it feels like any other rock: cold and hard. It reminds me of all the hikes I took back home in India, where I sat on rocky slopes to rest and felt the surface of the slumbering mountain beneath.

I look through other displays. The wooden cases enclose smaller specimens of similar-but-distinct minerals. I see clear crystals and rocks of various colors ranging from deep blue to turquoise, pale pink to dark red, golden yellow to tangy lime, and pale lavender to bright orange.

There is a mineral called barite that is shaped just like a rose, with all the petals in the form of crenulations, margins or contours with shallow, typically round notches or projections. An important ore of the element Barium, barite is used mainly for the production of paper, rubber and in x-rays. Here, it lies as a delicate mineral among its light-colored counterparts.

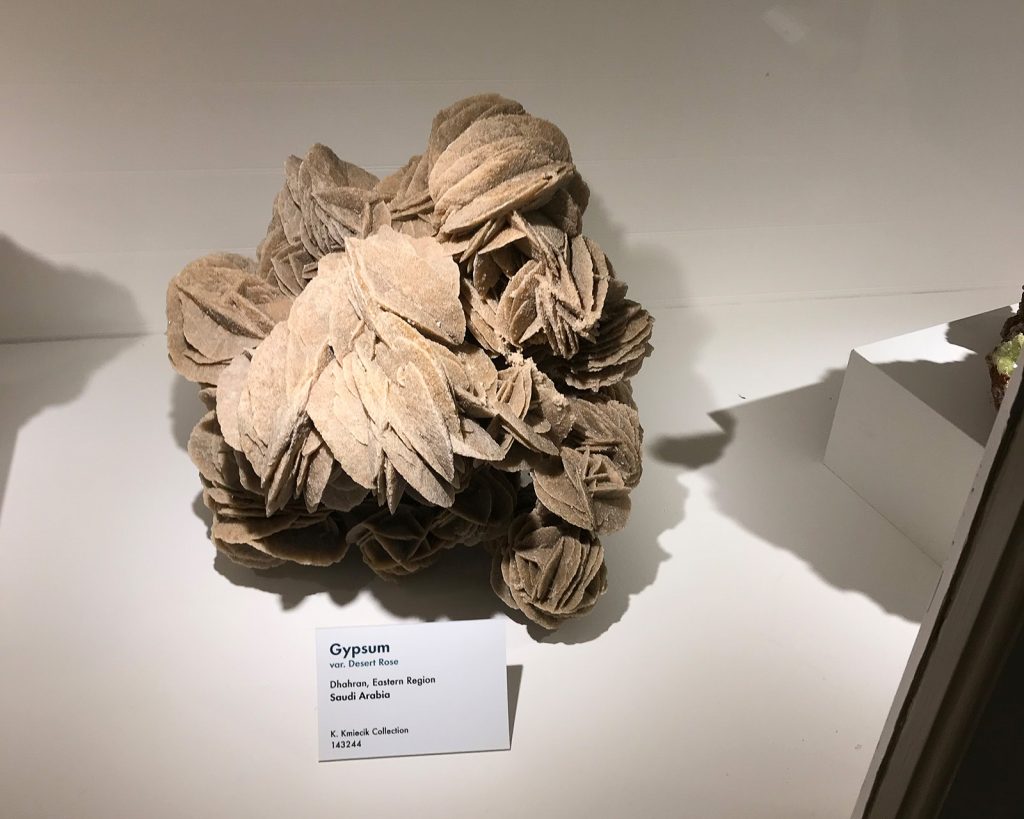

And who knew Gypsum, the main component of concrete, is so varied and beautiful? There are so many variations in Gypsum – one looks exactly like a sea urchin, one like a coiled roundworm and another like clams fused together. Forget Kryptonite, Superman; build your mansion out of Gypsum. It’s much cooler and brighter compared to kryptonite.

I am amazed by the collection of minerals on Earth and of Earth in general. What we see is only the surface, for the ground below has treasures: various unusual rocks and minerals. I look around the exhibition room once more before I leave. As I climb down the stairs, I take with me the fruits of a curious and open mind.