By Audrey Martin

Boston University News Service

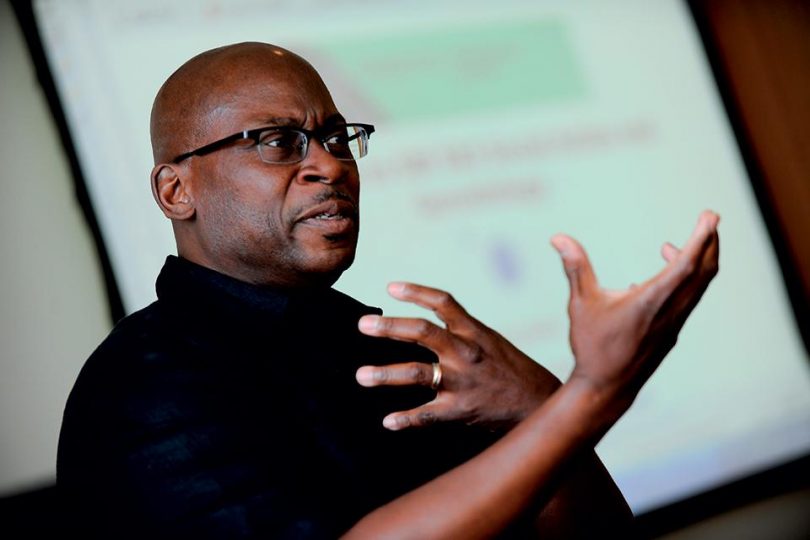

For Gary Bailey, a longtime advocate for Black and LGBTQ rights, it has never been a question of whether to become an activist, but rather how could he not? How could he look at the state of the world — particularly how the people who looked and thought like him were being treated in America — and not do something about it?

“I believe that change starts with me,” Bailey said. “And I can’t ask someone to do something that I’m not in the trenches doing myself. I believe in the statement that none of us eat the fruit from the trees we have planted ourselves — I’m planting trees for other people to eat from.”

Bailey, who was a child during the civil rights movement in the 1960s, said he was inspired from an early age to begin advocacy work for the injustices he was facing at the time. To him, this kind of work has always been personal.

“If it’s not personal, then it becomes something that you can add on and take off,” Bailey said. “I lean into the things that are part of my life. I’ve been involved in AIDS work early on, because I wanted to create and make sure the systems were there if I ever needed them.”

And up until very recently, Bailey said, those systems were nonexistent in the United States.

“As a queer kid, growing up we had to build the systems that exist today,” Bailey said. “They didn’t exist. They weren’t there. We built the infrastructure that put us in good standing.”

Bailey now works as an assistant dean for community engagement and social justice at the College of Social Sciences, Policy and Practice at Simmons University. Throughout his career, he has served on a number of social justice boards and committees, including serving on boards for former Massachusetts Governors Charlie Baker and Deval Patrick.

More recently, he has focused his work on living at the intersection of varying identities, mainly as an older Black, queer man.

“Aging gets pushed to the back of the space, and it used to be that we were supposed to, as older gay people, just go off and have other people forget that we existed,” Bailey said. “But we’re not going quietly into that night anymore. It’s just not the generation for that. We’re healthier. We look better. We feel better. We’re still here and are proud to be able to talk across the generations.”

On Feb. 10, Bailey hosted a panel discussion called “Black, Queer, and Aging” that saw Bailey inviting other Black and queer activists to speak on what it means to live with these intersectional identities.

Quincy J. Roberts, the LGBTQ+ community liaison for the Office of Neighborhood Services in Boston and one of the panelists, spoke about the necessity of reaching people who have different views than him.

“I hate preaching to the choir,” Roberts said. “When you’re talking about race, I don’t wanna talk to a room full of Black people. I wanna talk to this room. More events where, if you are going to talk about race or social economic status, about a BIPOC queer people, we need to have a different audience.”

Chastity Bowick, the executive director of the Transgender Emergency Fund of Massachusetts, emphasized the importance of educating other LGBTQ people about the issues of transgender individuals.

“If we don’t start having these conversations, breaking down these stigmas and stereotypes, we’re never going to get anywhere,” Bowick said. “There is a stigma that is rooted in our community that’s plaguing us, and we need to address that. I feel like when I’m bringing this up in settings like this or other settings with other gay and lesbian identifying individuals, they say ‘Oh that’s not really an issue,’ and it gets washed under the rug. No, it’s an issue because my people are dying.”

Having lived through more than a few tumultuous times in American history, Bailey said that now more than ever, young, passionate activists are vital.

“I get up every day hopeful because I know I can make change in the world,” Bailey said. “I know, as a social work clinician, that when things are uncomfortable, that’s where change happens. And the opportunities for change reside. I also know that we’re going to be all right and that as a Black, queer man of a certain age that I’ve seen enough to know that I’m still here and people whom I love, we’re still here.”