By Shannon Larson

BU News Service

WEYMOUTH – They awake early in morning, often still exhausted from the long hours worked the day before. Gone are the times when they could don their own colored scrubs or wear their hair down.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, the nurses of South Shore Hospital now drive along the quiet roads in their everyday attire – they will suit up in multiple layers of protective gear and clean light blue scrubs upon arrival – and brace themselves for what awaits them.

The parking lot at the Weymouth hospital was once the first obstacle staff encountered, said attending nurse Amy Timmons. An empty spot could be hard to come by, and visitors often complained they had trouble finding a space.

But guests are no longer allowed inside to prevent the further spread of the virus, so most spaces sit empty.

“That was what hit us the most,” said Timmons, 45. “We’d look out the big windows, and we’re like, ‘Wow. There’s empty parking spaces.’ That’s crazy.’”

It’s when they walk through the main doors, she said, that the “controlled chaos” begins.

Like other health care professionals on the front lines of this crisis, they have made a career of fixing people and returning them to their loved ones. The patient may have a few more prescriptions, stitches or bandages than when they came in, but the worst is over.

But in the time of the coronavirus, when the numbers of new deaths and cases remain stubbornly high in Massachusetts – and a vaccine remains out of sight for maybe a year or more – the daily influx of patients and lives lost can feel like an impossible race against time.

“You’re fighting a terrible war and at times you feel like you’re not winning,” Timmons said. “That’s what’s hard for nurses. You usually make a lot of them better, and then they go home. We’re not seeing a lot of that.”

The morning hours: From dawn to arrival

Geri Petrillo, a nurse in the critical care unit, is an early riser. When she wakes up around 4:30 a.m., the 50-year-old hopes it’s not with a headache.

The pounding sensation has become a familiar pain among staff, she said. The rise in coronavirus cases has necessitated an increase in demand for extra help – and many, including Petrillo, have been working overtime to compensate.

Her routine now includes sitting on the edge of her bed and pondering how the day will go. If she worked the day prior, she worries about the patients she looked after: How are they now? What care will they need today?

On the way from her home in Plymouth, Petrillo puts on her own makeshift concert – she prefers the music loud, and she always sings along. Country music – Keith Urban, specifically – is her go-to choice. She will often stop by Dunkin’ for an iced coffee, and if a friend happens to be working the same shift that day, they will “talk in the car the whole way up.”

“When I get to work I’m always there early,” and by at least a half-hour, Petrillo said. “I look up my patients – everything about them – because I like to know more than I need to know. I like to know the whole story.”

Beth Sault, a 42-year-old nurse in the emergency unit, agonizes all night about what she will walk into the next day. She loses sleep over what she has seen – the overwhelming number of patients, the loss of life, the despair of patients unable to be with family – and what she will encounter next.

“The fear that these patients and families feel – it’s crazy,” Sault said. “I’m good one minute. The next minute, I just cry for no reason at all.”

She has worked in the department for more than a decade, but is at a loss for words when describing the current scene.

During her 40-minute drive from Taunton, she tries not to think too much. It’s a period of calm. Like Petrillo, she drinks coffee and listens to music. Walking in the door “is when all the emotions start going” as people give her a thumbs-up or other signs of support.

Upon entry, Sault gets screened “every single day” to ensure she and other staff have no symptoms of the virus

“It’s so surreal,” she said. “I never thought I would be living my life being screened to go in through work to make sure that I’m healthy enough to do my job.”

Encouraging signs, penned by little kids to adults alike, are scattered throughout the hospital. There is not a soul in sight without a mask on.

Timmons used to be one who always ate breakfast at work. These days, she allots extra time in her morning routine to eat at her home in Abington. She uses the time to clear her mind and prepare.

“I just try to keep my mind empty of everything and try not to dwell or think about a lot of it until I’m there,” Timmons said. “That has helped.”

She tries to maintain that clarity and stay positive on the ride to the hospital, and when she enters its doors. The day is going to fly by, Timmons said, and it’s crucial to remain in the right head space because “there’s going to be so many emotions and it’s going to be so physically heavy.”

Timmons said she arrives around 6:30 a.m. on a typical day.

“And the chaos – I hate to say it – I call it controlled chaos now. The chaos starts.”

Amid a 12-hour shift: ‘It’s a grueling, grueling day’

The first part of a shift can be likened to a workout in its own right: the nurses gear up.

Prior to the pandemic, Timmons worked on what was mainly an orthopedic floor, where patients underwent surgery for hip or joint replacements. But now Emerson 5 has been converted into one of the coronavirus units.

In the middle of the floor, what once served as a rehab gym has been converted to a changing area with screens. On a table lies scrubs of all sizes, and a laundry basket is positioned nearby. In the hallway there is a cutout with clothesline stretched across it, and inside the paper bags hanging off the line are respirators and face shields for the nurses.

Timmons, and the team of nurses she oversees, each grab a bag before heading in to change.

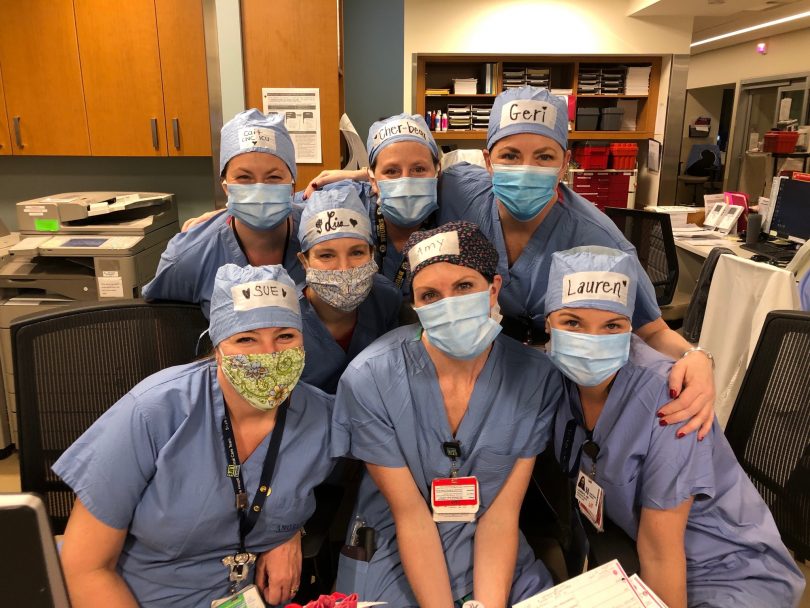

While they all work in different areas at South Shore Hospital, the three nurses and all of their colleagues are required to wear the same uniform: light blue scrubs, a hair net, a scrub cap, a respirator mask, a face shield, a gown and two pairs of gloves.

“We’re covered in all this gear,” Timmons said. “No one ever knows anyone. You’re kind of getting in people’s faces to know who they are because you’re so covered.”

Once they have settled in, the real work begins.

South Shore Hospital, a leading medical care provider in the southeastern part of the state, was bustling with activity before the coronavirus pandemic. Visitors, typically relatives or close friends of patients, walked through the halls, provided company at bedsides or grabbed a meal in the cafeteria.

But the pandemic has rendered this impossible. Only patients and staff now are allowed inside the hospital walls.

The tables in the cafeteria sit empty. The hallways are quiet, though the hospital units are anything but. Patients are alone, aside from the constant accompaniment of a nurse – and often now because of the pandemic, another person receiving medical attention in the bed beside them.

“It’s very empty. It’s very eerie. It’s frightening,” Timmons said. “It’s kind of like a ghost town. Never did you ever think that you’d have an entire big hospital like that and you would see not one family member.”

Their respective units have been transformed to meet the demands of the unprecedented public health crisis, with patients now doubling up in rooms and the number of nurses working a shift increasing significantly.

The critical care unit at South Shore Hospital is only about three-and-a-half years old, Petrillo said. When it first opened up, the nurses were amazed by the size of the rooms.

“When we moved over, we were like, ‘Oh, my god. These rooms are so big. Why are they so big?’” Petrillo said. “And somebody said, ‘Oh, you know. God forbid if there was ever like a mass casualty or something, and they needed to put two beds in a room.’ And we were like, ‘That’s never going to happen.’”

But now the rooms in the unit, which went from 24 beds to 48 beds to care for as many coronavirus patients as possible, don’t look as big anymore, Petrillo said. Each room has two ventilator machines squeezed in as well, and when nurses enter – who could be in there for hours on end before exiting – they shrink even further.

When the changes first occurred, Petrillo – like many others who could not begin to fathom what was to come next – thought the precautionary measures were just that: precautionary. Then things started ramping up, hitting states such as Washington and New York. The Biogen meeting in Boston brought it to the front door.

Initially there were a few rule out cases, then one or two patients testing positive for coronavirus around mid-March, Petrillo said. She recalled being off for a couple of days, and then returning on a Sunday night to a whole other ballgame.

“I just saw our Sunday night into Monday start to ramp up, and it has hasn’t stopped since then, like we were at max capacity,” she said.

Inside the room, the mask is always on, Petrillo said. Nurses have a hard time breathing, and an even more difficult time trying to communicate with patients through the protective layer. For up to three hours, Petrillo can remain stationed in a single room, giving the person she’s looking after their medication and turning them over.

If she needs something, Petrillo writes on the glass door with dry-erase markers, and one of the many nurses working in the unit assists.

“It’s a grueling, grueling day,” she said.

If a nurse is to leave the room of a patient that they have been caring for, Timmons said, they must sanitize their gloves to wipe down the face shield, then repeat the step again to get the gown off. Whereas nurses would never reuse a respirator before the pandemic, she said they now wear one for every five shifts.

There’s just not enough protective masks to go around as before, she said, but noted the gear shortages – a widespread issue among hospitals in the beginning – has significantly improved over time.

“I feel that I’m more protected there than I am if I was out in the community,” she said.

With families unable to be there in-person, nurses have had to step up and fill those shoes as best they can – serving as both a caretaker and emotional support.

Sault, who works in the emergency unit, said coronavirus patients become “sicker and sicker and sicker” by the minute.

The absence of relatives in the room has been the most challenging part, she said. Phone calls come in by the dozen with families looking for updates and sharing concerns. In the age of coronavirus, FaceTime has become the substitute for real-life contact, with Sault and other nurses arranging times for mother and father, brother and sister, husband and wife to see each other.

The conversations are often heartbreaking to watch, she said.

“I can’t imagine being in that bed and not having my family there with me if I was sick,” Sault said. “We’ve dealt with tragedy before, but we haven’t dealt with tragedy every single shift that we’ve gone into. This is now the new norm.”

Timmons recently cared for an elderly, but “very independent” and “very active” man. The coronavirus wreaked havoc on his body. He was on as much oxygen as she could provide, and he chose not to have a breathing tube.

“When the patient looks you in the eyes and tells you that he needs to die,” Timmons trailed off.

The only contact available for him with his wife of many decades was through an iPad that Timmons brought into the room. Looking at her husband via a video screen, she told him that she would have done her hair if she had known they would be talking.

“And he says, ‘You’ve always been beautiful to me,’” Timmons said. He gasped for air and said goodbye for the last time.

The breaks are few and far in-between, the nurses said. But in the rare moments they do have to step back, a large part of what helps motivate them throughout a shift are the unrelenting acts of kindness demonstrated by the community.

Restaurants donate meals, including chicken burrito bowls and gnocchi dishes. Sidewalks outside the hospital have chalked messages of encouragement such as, “If you are just leaving, thank you for what you’ve done.” Residents host drive-by parades and pen heartfelt letters thanking the nurses.

“To see how many kind people in the world there are – it really is something,” Sault said. “It’s unbelievable.”

The impact of the pandemic on how they perform their jobs – and even as people go about their daily lives once the virus recedes – will likely be lasting, if not permanent, the nurses said.

“This experience will change all of us,” Petrillo said. “It already has changed all of us.”

Going home: ‘You get in your car and you just let it all out’

After her shift has ended as of late, Petrillo goes out outside and just stands there, breathing in the fresh air. When Sault is done, she is completely exhausted and longs to see her kids. When Timmons gets into her car to drive home, she cries more than she ever thought possible.

“You just let it all out because you’re now their everything,” Timmons said. “You’re used to patients going downhill. You’re used to people getting sick. I have seen death. But never like this.”

Before the pandemic, the women could go home and relax. They could hug their families – all three have children at home – and do simple things like sit down or have a snack. But now the virus, and the looming threat of infecting those they care for the most, hangs above their head.

Sault has three boys: ages nine, 13 and 24. She no longer gives them kisses, and it kills her. She tries to keep her distance out of fear she could be a carrier. All of her work gear stays in the trunk of her car, her shoes remain in the garage. She bleaches everything, and door handles get wiped down constantly.

“I do still give them big hugs,” Sault said. “Because I have to.”

But first, they rush to the shower and wash the day away.

All three nurses noted that the transition from working a 12-hour shift or longer at the hospital – where the work is constant and emotionally draining – to returning home, and largely being unable to travel or do much of anything – can be disorienting.

Both Sault and Timmons, who has an 8-year-old daughter, also have to homeschool. It adds stress to an already taxing job, Sault said, especially as she attempts to limit her contact with her children to minimize their risk of infection.

Petrillo comes from a large Irish family, and she said it’s been helpful for her to de-stress by talking with her cousins and siblings from all over – including New Jersey, New York and Ireland – via Zoom.

But who she unloads to are her work friends.

“They’re the ones we can really talk and get into everything with,” she said.

Timmons said she carries deep concerns over how nurses and other medical professionals will be affected mentally – and how they already have been – because of what they have experienced during the pandemic.

She had four patients die in a single day from the coronavirus. Timmons said the memory will never leave her.

“We were talking yesterday at work about how nurses are now going to have PTSD from this,” she said, adding that she hopes colleagues seek therapy or help if they need it. “Because this is something that no one should have to see.”

Earlier this month, a top emergency room doctor who was treating coronavirus patients at a New York City Hospital died by suicide.

The father of Dr. Lorna M. Breen told the New York Times that she “tried to do her job, and it killed her.”

It’s especially frustrating, Timmons said, to see what she has and reconcile that with people proclaiming that the virus is not real and that the numbers of deaths are made up.

They are not seeing the number of patients being wheeled to the morgue, Timmons said. Nor are they seeing that the morgue is so full that the hospital has to have two refrigerator trucks. They are not bearing witness to patients who are holding their hands as they gasp for air because the virus has engulfed their lungs.

“You’re not these family members who are sitting at home, waiting for the phone call for us to tell them that their loved one has passed away because they can’t be with them,” she said. “I wish this was all a nightmare – a dream – that I’m going to wake up from and it’s going to be gone.”

Timmons, Petrillo and Sault all brushed off the notion that they were “heroes.” The circumstances may have changed – and dramatically – in the past few months, but it’s the same job as always, they said.

“I think we all signed up for this job,” Petrillo said. “I feel like it’s our role as nurses to rise to the occasion. We collaborate as a team, we work together as a team. It just happens to be our profession that’s affected right now.”

“It’s funny because if someone said to me, ‘Beth, you can pick anything in the world that you want to be,’” Sault said, “I would still pick a nurse every day. Everyday.”

“I bet if you talked to the majority of nurses, they would tell you, ‘We’re not heroes,’” Timmons said. “We’re just doing the job that we love.”

Before they go to bed in the evening, they set their alarm for work the next day. It’s the same thing all over again tomorrow.

This article was originally published in The Patriot Ledger.