By Devyani Chhetri

BU News Service

BOSTON – Whether they use the Massachusetts Bay Transit system or prefer driving to work, professionals in the Boston area will say they are in need of a transit crutch to make their next commute.

Ana Hernandez, 50, has always relied on the MBTA to get around the city. However, on most days, she feels that her commutes leave her drained.

Hernandez spends roughly four hours a day traveling to and from her workplace near Fenway Park. This includes the time she leaves her house in Dorchester to walk to the closest T station, wait for the train, ride it, walk to work and then repeat the process in reverse after her shift.

“And that’s on a good day, if the cold doesn’t mess with the train,” Hernandez said with a smile.

It would be easier for her to work closer to home, she said, and perhaps a car would cut her commute time in half. But the conveniently located eatery she used to work in has shut down, and owning a car can be expensive.

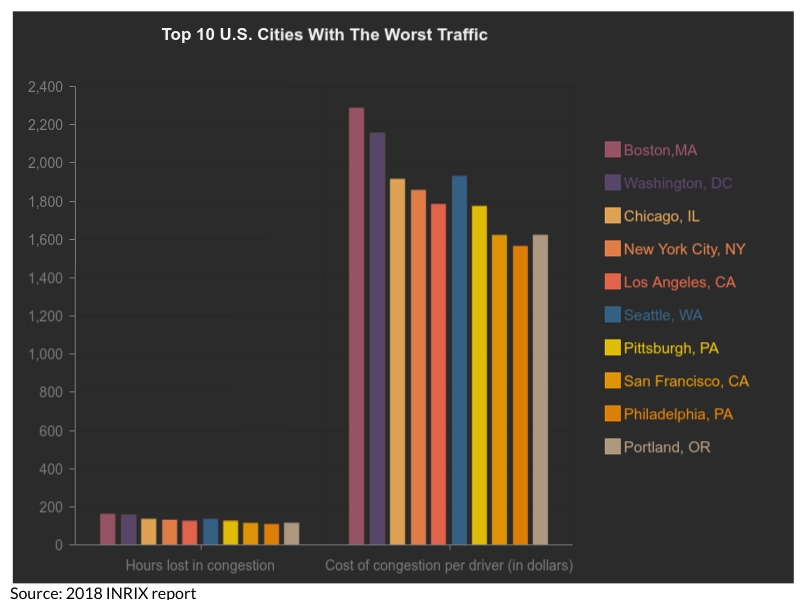

Boston ranks highest in the country and 8th worldwide when it comes to a loss of productive time due to commuting, as per the 2018 INRIX report, a data analytics firm that collects traffic data.

Beset with an ailing public transit service and the long hours spent idling in traffic, it costs every Bostonian driver – or the ones passing through its roads – $2,291 when they hit congestion.

Then there’s the issue of climate change.

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker started 2020 with a resolution to achieve net-zero carbon emission by 2050 in his State of the State address. In late January, the Senate passed a comprehensive climate policy package: a trio of bills for a greener transportation system.

MassDEP data showed greenhouse gas emissions through fuel consumed by transportation have declined by nearly 6% in 17 years since 2000, when it was at 32.0 MMT, compared to 2017’s 30.4 MMT.

With the burgeoning usage of Uber and Lyft rides and nearly 380,000 more employees in the city since 2010, the state would have to do more if it wants to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions by the deadline.

Councilor Lydia Edwards believes a transit benefit ordinance could help pave the way for that – a rule that would allow companies of a certain size to provide subsidized CharlieCards using pre-taxed income so that more workers might be encouraged to take the T.

But not everyone is on board with the idea.

“We have always and will continue to encourage our employers to incentivize their employees to use public transportation,” James E. Rooney, President & CEO of the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce said in an email to BU News Service. “However we are reluctant to support any kind of mandate on employers.”

Transit benefit are already in place in Washington, Chicago and New York, which respectively rank second, third and fourth after Boston in the INRIX report.

Washington employees are entitled to three types of transit benefits. To cover commuting costs, they can either set aside $265 from their paycheck, be reimbursed the same amount through company travel vouchers or benefit from an employer-sponsored cab or bus ride.

Meanwhile in Chicago, employees can set aside up to $260 of their gross income for transportation. The advantage for employers, as per the law, is that providing these subsidies will also reduce the taxation imposed on them.

But Bostonians remain unsure about the ordinance’s potential to succeed.

Lost hours have also raised issues of job retention. Last year, a poll conducted by MassBio found that 60% of biotech workers wanted to leave their jobs because of the daily hassle of commuting.

Chase Matheson, 34, left his job after a year experiencing traffic congestion, and he doesn’t think that a transit benefit ordinance could do much.

“The drive from Medford to Waltham would sometimes go beyond an hour and a half one way,” Matheson said. “I really tried for a year. My company even gave me a raise. But I still left.”

As for Hernandez, although her employer occasionally has paid for her Uber rides during snow days, her workplace does not offer remunerations or commuting aides to its employees. When asked if a transit benefit ordinance would make a difference in how she commutes, Hernandez smiled.

“It wouldn’t hurt to take the occasional Uber,” she said. “But the T still has a long way to go so I’m not sure. I don’t have an option.”

[…] could amount to almost $11,000 per employee due to lower office maintenance costs and reduced transportation reimbursement expenses. Additionally, the chances that an employee might be absent from work could decrease, […]