By Sammie Purcell

BU News Service

There’s a moment in Charlie Kaufman’s new film, “I’m Thinking of Ending Things” that has stuck with me. A character comments on how people are emotionally affected by art, saying: “How can a picture of a field be sad without a sad person looking sad in the field?”

Another character tries to explain how the feeling associated with art comes from the viewer, not the image. The first character dismisses this notion – “That’s over my head, I guess.”

This exchange perfectly sums up just about any Charlie Kaufman movie. Nothing is ever clear, but as with a piece of abstract art, or a beautiful landscape, you’re hit with a tangle of unyielding emotions anyway. That sense of, “I’m not quite sure what this is, but it sure is making me feel some type of way.”

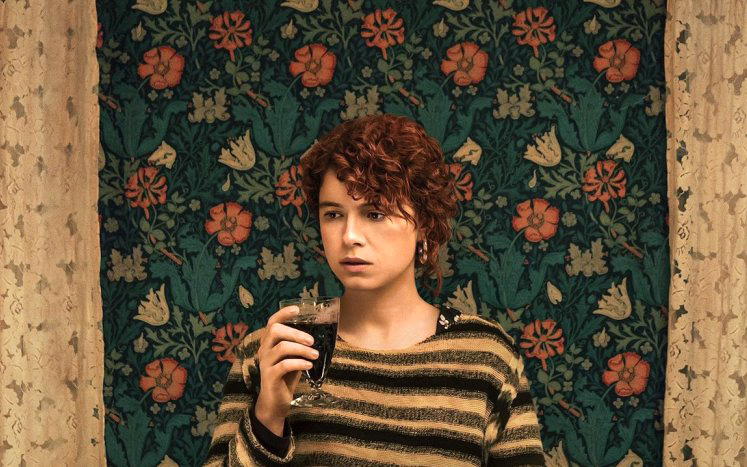

The story is simple enough – an unnamed young woman (Jessie Buckley) travels with her boyfriend Jake (Jesse Plemons) to meet his parents (Toni Collette and David Thewlis). The couple drives to their house, has dinner and leaves.

But what actually unfolds onscreen is not that simple. Every action, every conversation, every stylistic choice, is bewildering, to say the least. For that reason, it’s a movie that warrants a second (or third) viewing. Adjacent to the main plot, there’s a janitor, a high school production of “Oklahoma,” and a dog that will not stop shaking. Costumes change without warning. Characters seem to be able to hear other characters’ thoughts. It’s the type of strange that has you furrowing your brow and frequently letting loose a confused laugh or mystified, “What?” By the end, you might be at a loss for what exactly just transpired.

So, if it’s so unclear, why do I feel so acutely awful? How can a movie be sad without a sad person looking sad in the movie?

I have seen this movie three times, and I am still not quite sure how to interpret it. But I am sure that it makes me feel achingly melancholy. I’m thinking of getting older. I’m thinking of the parts of myself that I don’t like. I’m thinking of what I’ve accomplished and the frightening notion of never being better than I am now. No one in the film explicitly said any of these things, but I am still thinking of them.

This unbridled ability to make viewers cry, laugh and contemplate their very existence makes Charlie Kaufman an incredible filmmaker, especially when he’s interrogating the inner psyche of a frustrated man. The mechanics of the plot and how Jake and the young woman fit together become clearer with more viewings, but this is a movie that does not beg to be understood – rather be felt. Kaufman is not in the business of telling the audience how they should feel. If you spend your time trying to understand every minute detail, you lose that emotional and deeply personal viewing experience.

The film explores several emotions and themes – parental relationships, romantic relationships, loneliness, how we measure success, aging – but what I keep coming back to is the awful pit of hopelessness I felt sitting in my stomach as the credits rolled. This film treats hope, much as it treats time, sadness, resentment – everything, really – as a human construct.

“I suspect humans are the only animals that know the inevitability of their own death,” the young woman says at one point. “Other animals live in the present; humans cannot. So they invented hope.”

Kaufman presents this hopelessness in every image and piece of dialogue, from Jessie Buckley staring almost viciously into the camera as she recites poetry about the foreign feeling of returning to your childhood home, or the shot of an iPhone that’s suddenly devoid of pictures or personal touches. However, he portrays this feeling most vividly towards the final third of the movie, when Jake and the young woman are driving home.

In the car, Jake brings up what he calls the “lie of it all.” The lie in question? Well, there are many: “That it’s going to get better. That it’s never too late. That God has a plan for you. That age is just a number. That it’s always darkest before the dawn. That every cloud has a f*cking silver lining. That there’s someone for everyone.”

Jesse Plemons delivers this monologue almost fully engulfed in darkness, with brokenness he hasn’t really exuded until this point paired with looming aggression that has simmered beneath the surface the whole time. It’s unexpected and effective. The anger comes from feeling duped by this thing called life – from being able to see the finish line and suddenly forced to reckon with the possibility that you didn’t really do anything with the time you had.

This moment makes clear why the rest of the film feels so daunting. All those moments where you laughed uncomfortably or felt an anxious prickle on the back of your neck – it’s because you are forced to wrangle with those fears just as much as the character. The fear of getting older each day, until lucidity finally escapes you. Until you’re so old that there is nothing to look forward to, all you can do is look back at your regrets and the worst parts of yourself with resentment. If the platitudes we tell ourselves are lies, if we are so adept at reminding ourselves of our own failings, if the people we imagine love us can despise us so fully – then maybe the idea of connection is just that: a fleeting dream that can never be realized.

Your article seems like an echo of the movie, which is probably how all reviews are supposed to flow. Except it also feels that way, so I guess your interpretation has captured the essence of the film.

You’ve piqued my interest. Good job.

It misses the point of life.

Banal People with no inner spiritually; living with their heads up their own a$$e$

Nice atmosphere and imagery.