By Hannah Schoenbaum

BU News Service

BOSTON – Massachusetts recorded the fourth-highest number of anti-Semitic incidents of any state in 2018, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents, prompting lawmakers to propose that all schools teach students about the Holocaust and other genocides.

Jewish students throughout the commonwealth have repeatedly encountered anti-Semitic slurs, been told their families should have died in the Holocaust and discovered swastikas scrawled on the bathroom walls of their schools, the ADL reports.

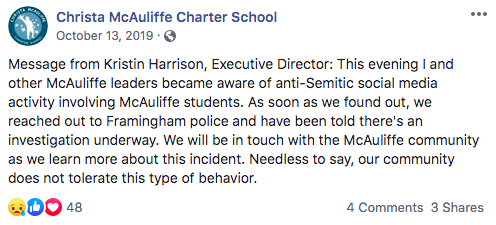

In just the last two months, a middle school student in Great Barrington threatened Jewish students with an alleged kill list and two students at Framingham’s Christa McAuliffe Charter School circulated a “Kill the Jews” Snapchat group.

Recognizing schools as hotbeds for anti-Semitism, state Rep. Jeffrey Roy, D-Franklin, and Senate Ways and Means Chairman Michael Rodrigues, D-Westport, filed the Genocide Education Act, which would require every school district to adopt genocide curriculum that addresses “the notion that national, ethnic, racial or religious hatred can overtake any nation or society, leading to calamitous consequences.”

Before Massachusetts students graduate from high school, they would be required to learn about acts of genocide including, but not limited to, the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, the Pontic Greek Genocide, the Ukrainian famine genocide known as Holodomor and recent genocides in Cambodia, Bosnia, Rwanda and Sudan.

“We hope, in the long run, that we will have a generation of adults that will have been exposed to this type of education so it will improve humanity,” Roy said. “In the short term, we hope that it heightens awareness of the impact of some of the anti-Semitic events that we’ve seen here in Massachusetts.”

Ninety-four co-sponsors have signed onto the bill, which is currently before the Education Committee.

Roy said he thinks the bill has a “tremendous level of support” and anticipates a favorable outcome from the committee. If passed, Massachusetts will become the 13th state to require some form of Holocaust or genocide education.

The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education adopted a new history and social science curriculum framework in June 2018, which includes materials on each genocide mentioned in the legislation. Though teachers are encouraged to use the resources outlined in the framework, they are not required to teach specific lessons.

“We’ve noticed an uptick in the number of anti-Semitic events and other troubling issues out there and resigned ourselves to the fact that it wasn’t simply good enough to have the curriculum frameworks incorporate genocide education because those are voluntary,” Roy said. “If a school district decides they don’t want to teach it, there’s currently nothing compelling them to.”

Rodrigues, who represents the First Bristol and Plymouth district in southeastern Massachusetts, said he became committed to fighting the local resurgence of anti-Semitism after a Jewish cemetery in his district was vandalized earlier in 2019.

On March 17, 59 gravestones at the Hebrew Cemetery in Fall River were defaced with swastikas and anti-Semitic phrases such as “Hitler was right” and “Expel the Jews,” according to the Fall River Police Department. Hundreds attended a vigil at the cemetery the following week, but Rodrigues recalled seeing very few young people in the crowd.

Anti-Semitism has been particularly prevalent among younger generations. According to the ADL’s Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents, there were 59 incidents of anti-Semitism in Massachusetts K-12 schools in 2018.

“The majority of anti-Semitic incidents we’ve tracked in the last two years have occurred in middle and high schools,” said Robert Trestan, director of the ADL’s New England chapter.

Although the number of reported incidents in schools declined slightly from 2017, Trestan said the figures are still historically high and of deep concern.

Violent attacks against Jews have increased since 2017, which the ADL sees as an indicator that “perpetrators feel emboldened to cross over from acts of harassment and vandalism into violence,” the audit report states.

Trestan said these incidents demand a proactive approach. Rather than responding to anti-Semitism when it occurs, he recommended educators focus on engaging students in conversations about how unchecked hate can proliferate through communities.

“Learning about genocide, in many ways, is connected to global safety,” Trestan said. “It’s critical that Massachusetts high school students and everyone in the community have the knowledge, the confidence and the education to be able to stand up to all forms of hate.”

The Genocide Education Act tops the ADL’s list of legislative priorities. Supported by both the Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents and the Massachusetts Association of School Committees, the ADL assembled a coalition that has been advocating on behalf of the bill.

“This is a message to schools that the framework for genocide education that is of high quality should not sit on a shelf or a computer server,” Trestan said. “It should be taught in the classroom. And that’s effectively what this legislation does. It takes the curriculum that’s already been written and it puts it in all classrooms.”

Though the Legislature’s Education Committee heard nearly three hours of public testimony from supporters of the bill at a packed hearing on Oct. 7, some community members have criticized the legislation for excluding the genocide of Native Americans by European settlers.

Rodrigues said Native American genocide “wasn’t talked about” when drafting the legislation.

“It wasn’t intentionally omitted,” the senator said. “That’s certainly something that can be added to the bill as it moves along. I think it would fit into the mode.”

The bill states that curriculum is “not limited to” the specified genocides.

Maria John, director of the Native American and Indigenous Studies program at the University of Massachusetts Boston, said she thinks passing this bill without an explicit mention of Native American genocide would be “very problematic.”

“I think to teach U.S. history within a framework of Native American genocide is simply to insist on teaching an honest engagement with the history of this nation,” she said, “and its origins in a history of colonization and settlement that actively sought to displace native peoples from their lands and saw a massive loss of indigenous life.”

The history professor, who teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on settler colonialism, said there is some debate between historians about whether the massacre of Native Americans should be classified as a genocide.

Discussions about America’s bloody history are often shut down by those who do not think the events can be grouped with larger genocides like the Holocaust, she explained.

“One of the benefits of putting the U.S. case into conversation with these other genocides in the proposed legislation is it does reinforce this message for students that not all genocides look the same,” John said.

Regardless of the criticism, John said events such as the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864 – in which U.S. soldiers mutilated and killed hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho people in southeastern Colorado – fall under the globally recognized definition of genocide.

In 1948, the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defined genocide as killing or harming members of a community “with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

“Even if we want to leave the question of whether the U.S. fits the mold of genocide up to debate,” John said, “I think the more basic underlying point is that to not even present this way of understanding U.S. history within the education system is really to perpetuate a massively incomplete picture of the history of this nation and, in doing so, I think to do a really huge disservice to our students.”

John said many of her students from around Massachusetts feel frustrated that they did not learn about the native origins of their hometowns while in high school, which she sees as an indicator that the state needs to expand its Native American education.

For educators who want to improve how they teach Native American genocide, John recommended focusing on stories of strength and survival, in addition to stories of tragedy. Through primary source documents and the many historical sites in Massachusetts, John said teachers can connect past and present history to teach students about the Native Americans who are still around today.

“Without downplaying the violence of settler colonialism, I think if teachers can also think about approaching this from the perspective of ongoing histories and indigenous resistance, then this has the added benefit of stressing the survival of indigenous peoples,” she said.

Similarly, Roy said he hopes the legislation will challenge educators to improve how they teach stories of genocide survival once the remaining survivors die off.

“For years, we had people who survived the Holocaust, who were living history, that would go out and speak to students and talk about what they experienced in these camps,” Roy said. “But a lot of these people are now either too frail or have passed on, so there’s very few firsthand accounts to talk about these issues.”

Ron Weisberger, director of the Holocaust and Genocide Center at Bristol Community College, said he thinks teachers should incorporate more documentaries, museum visits and memoirs, such as Elie Wiesel’s “Night” or Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl,” into their Holocaust curriculum.

“Even when we’re no longer able to bring survivors into the classroom, teachers still have many resources, even videos of survivors telling their firsthand accounts, that they can use to elicit a similar emotional reaction from the students,” he said.

Weisberger, one of the many educators who testified in support of the bill at the October hearing, leads genocide education workshops for regional teachers and students. His center has also hosted educational conferences about the Holocaust, Native American genocide and the genocide in Cambodia.

Though some educators have shown enthusiasm about improving their lessons on these subjects, Weisberger said others have no incentive to make improvements without a legislative mandate.

This article was originally published in the Worcester Telegram.