By Prithvi G. Tikhe

BU News Service

BOSTON – The devastation in Massachusetts related to the opioid crisis has led a state lawmaker to propose a tax on the legal purchase of opioids from manufacturers, with the goal of combating the epidemic by dedicating the revenues generated to address substance abuse prevention and treatment.

“This is a step in the right direction and our continued fight to try to win this battle with substance use disorders is of the utmost importance for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,” said Rep. James O’Day, D-Worcester. “We have to be able to do a better job of preserving families and lives.”

O’Day introduced the bill at the start of the 2017-2018 legislative session that would impose a tax equal to one cent per milligram on the sale of any taxable active opioid by the manufacturer, producer or importer. The bill was placed under review in February, indefinitely postponing action.

Under the proposal, there would be no tax on drugs prescribed for medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction. Eligible patients – those prescribed a taxable active opioid for pain related to cancer, hospice care, incapacitation or facing death – would receive a rebate for cost increases related to the tax. Ineligible patients – those suffering chronic pain from other conditions – will likely pay a higher amount.

A research report indicates that more than 1.5 billion people worldwide suffer from chronic pain, including 100 million Americans, a number more than diabetes, heart disease and cancer patients combined. Common chronic pain complaints include low back pain, headache, neck and arthritis pain.

Tax revenues would be used exclusively for treatment of substance abuse, including opioids, in the commonwealth and establishing programs like new addiction treatment and sober living facilities.

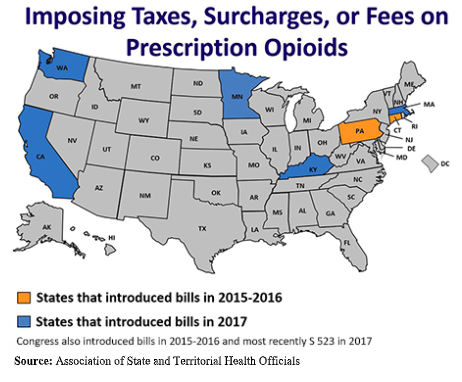

Since 2015, legislators in at least seven states, as well as Congress, have introduced 15 bills to finance substance use disorder prevention and treatment activities by imposing a surcharge (Connecticut and California), tax (Kentucky and Massachusetts), fee (Minnesota, Washington), or an assessment (Pennsylvania) on prescription opioids.

In the late 1990s, health care providers began to prescribe opioid pain relievers at greater rates because the pharmaceutical companies reassured the medical community that patients wouldn’t become addicted. This led to extensive misuse of these medications before it became clear that these drugs were highly addictive.

Opioids trigger the release of endorphins, “feel-good” neurotransmitters, which stifles the perception of pain and boosts temporary feelings of pleasure. When an opioid dose wears off, the patient wants to feel good again, often setting them on a path toward potential addiction.

Nationally, over 97 million people took prescription painkillers in 2015, according to survey data and over two million Americans are estimated to have a problem with opioids.

In Massachusetts, more than five people per day died from confirmed or estimated opioid-related overdoses over the first nine months of this year according to the Department of Public Health. There were 1,518 opioid deaths between Jan. 1 and Sept. 30, compared to 1,538 deaths over the same period in 2017.

In 2018, among the 962 opioid-related overdose deaths in Massachusetts 90 percent had a positive screen result for fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that has effects similar to heroin.

A big part of the problem is not having the availability of places for people to go for treatment, said Jacqueline Morse, 37, a veteran in long-term recovery and an opioid recovery coach at Assist, Educate and Defeat Foundation and Alyssa’s Place, a peer recovery center in Gardner.

“There are never enough beds at any time which ends up sending an addict who is willing to get treatment back out onto the streets,” said Morse. “This can sometimes be fatal.”

Although she supports the legislation, Morse hopes the bill doesn’t unfairly penalize patients with chronic pain who really need the medication. But every positive always has a downside and vice versa, she said.

That potential penalty also concerns Michael Schatman, adjunct clinical assistant professor at Tufts University School of Medicine, who said the tax will be passed on to the consumer in the form of higher co-pays.

“While 1 cent per milligram may sound trivial, patients on high-dosage opioids are often on disability,” said Schatman, who is also research director at Boston PainCare. “To them, an extra dollar or two each day over the course of a year may make purchasing quality of life-improving medications cost-prohibitive.”

When asked about medical marijuana being a viable option to treat chronic pain over opiates, Schatman emphasized that based on recent data regarding physical, cognitive, and psychiatric safety, in conjunction with the lack of empirical data supporting it for pain management, the notion that medical marijuana is safe and effective is “absolute baloney.”

Before passing such “draconian legislation,” legislators should be required to take a brief course in chronic pain – or at least read pertinent literature written by key opinion leaders, said Schatman, editor in chief of the Journal of Pain Research.

But O’Day doesn’t expect the tax to drive up the cost for chronic pain patients.

“This is not the intent of the bill whatsoever,” he said.

However, Lauren Deluca of Worcester, who founded the Chronic Illness Advocacy and Awareness Group after her own challenges in getting opioid painkillers for a gastro-vascular disorder that causes chronic stomach pain, disagreed.

“We have millions and billions of dollars on hand for the crisis already, so I question the motive to bring forth more bills for more money,” she said. “This bill helps fund more clinics and people who want to become executive directors and build businesses for themselves, but it does not help those with addiction.”

Deluca doesn’t think anybody would file a rebate voucher as proposed by the measure for, say, 50 cents. If there are two million such unclaimed vouchers for 50 cents each, that’s quite a bit of money for the state, she said.

As for chronic pain patients like herself, Deluca said, “It’s not a sin tax like the cigarettes; we need the opioids to be alive.”

But according to Andrew Kolodny, co-director of Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management, chronic pain patients should probably not be on opioids long term.

He said if a chronic pain patient takes an opioid every day for weeks and months, within the first week they become tolerant and will need higher doses in order to get pain relief, which causes a decline in their function.

Kolodny added that opioids are effective and appropriate for the eligible patients mentioned in the bill in which case patients are on low doses to ease suffering.

“This tax makes sense to me,” he said. “They are putting in writing that this money is for addressing opioids.”

On the contrary, Keith Humphreys, a professor of mental health policy at Stanford University and former drug policy adviser in the Bush and Obama White Houses, thinks the history of earmarked taxes is not very encouraging.

Humphreys said money from the tobacco settlement gets used to repave roads and taxes on alcohol that are supposed to fund alcohol treatment ends up funding new parks. If the state wants to fund substance abuse treatment, then they should create the funding and not count on a dedicated tax, he said.

The tax could fall on pain patients as well as the state’s Medicaid program, he continued, if the state is picking up a lot of these prescriptions.

“The state is just really taxing itself,” Humphreys said. “You know you could say, ‘Oh the state’s bringing in $100 million,’ but then that charge is coming onto Medicaid and in the end, they are not making anything.”

A better legislative model, according to Humphreys, is the New York state law, which charges companies that manufacture or distribute opioids in the state a collective $100 million per year. With such laws, no chronic pain patient will have to worry about price adversely affecting them and keeps the state out of it, he said.

Healthcare Distribution Alliance, a national trade association representing primary pharmaceutical wholesale distribution companies, filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York in July to block enforcement of New York’s Opioid Stewardship Act and testified in opposition to O’Day’s bill in the last legislative session.

In a statement, HDA said, “Using taxes to single out and punish an industry that does not develop or produce medication for a crisis with multifaceted, complex societal roots is fundamentally flawed. The proposed tax would ultimately raise the cost of and limit access to medicines for the citizens of Massachusetts.

“Further, such an approach would impose a significant burden on the pharmaceutical distribution industry that, as logistics experts, has no role in the prescribing, dispensing or manufacturing of medications. The entity already works collaboratively with state and federal regulatory and law enforcement agencies to assist in the prevention of drug diversion and abuse.”

“We flagged the taxpayer study only to highlight the growing impact of illicit drugs in Massachusetts and around the country,” said John Parker, senior vice president of communications at HDA. “The original legislative proposal was not designed to address this new and emerging reality.”

Schatman, who is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Pain Research, said data demonstrate that every year since 2011, opioid prescribing in the U.S. has decreased. The current opioid crisis is about illicit fentanyl and its analogs, which are flooding the streets. As physicians, for the most part, are no longer willing to prescribe opioids for chronic pain, many legitimate chronic pain patients are being forced to the streets, where they are purchasing illicit fentanyl products pressed into faux prescription opioids, he said.

“[Faux prescription] opioids are extremely inexpensive and deadly,” said Schatman.

Ross Marchand, director of policy at the Taxpayers Protection Alliance, agreed.

Marchand said that in states with high cigarette taxes, tax avoidance through arbitrage – the practice of taking advantage of a price difference between two or more markets – is common. Criminal organizations have been caught buying cigarettes in low-tax states such as North Carolina and selling them in high-tax states such as New York, he said.

“Whenever you see taxation and prohibition, you see these sorts of unintended consequences that opens up market opportunities for illicit organizations trying to get a buck to fund terrible activities like human trafficking and drug production,” he said.

O’Day plans to refile the legislation in the next session.

However, Deluca said the bill is not addressing the real drug problem, fentanyl.

The addiction community and the pain patients have starkly different needs, but the opiate is what they have in common, she said.

“An opiate is vital for one and horrible for the other and we need to recognize that vital difference and start respecting that line,” said Deluca. “There is an equitable way to help both communities without penalizing one another.”