By Ying Wang

BU News Service

Yin Yu Tang was unoccupied when Nancy Berliner first saw the house in Anhui Province, south of China, in 1996. On her trip shortly afterwards, the Huang family, who had lived there for eight generations, decided to put the house up for sale. An independent scholar of Chinese art from Massachusetts, Berliner transported the approximately 200-year-old house to the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem because the museum happened to be preparing for an extensive expansion.

An agreement was established between the Huang family, the local cultural relics administration and the Peabody Essex Museum in 1997. The 16-bedroom building was dismantled into 2,735 pieces of wood and 972 pieces of stone, as well as the home’s furnishings, and delivered to Massachusetts in 1998.

Since the summer of 2003, Yin Yu Tang — which roughly translates into a desire to shelter many future generations — has been a gem at the Peabody Essex Museum. The civic house represents a culture of renowned Hui merchants as well as Hui architecture featuring wood, brick and stone carvings.

“[Yin Yu Tang] is a fortune child who was given blessings to promote Chinese culture for its siblings left in Anhui,” said Shukai Wang, the project manager of Yin Yu Tang, in a documentary made by the museum.

While Yin Yu Tang is unique in the U.S., Wang said the house would not stand out in Anhui Province in eastern China.

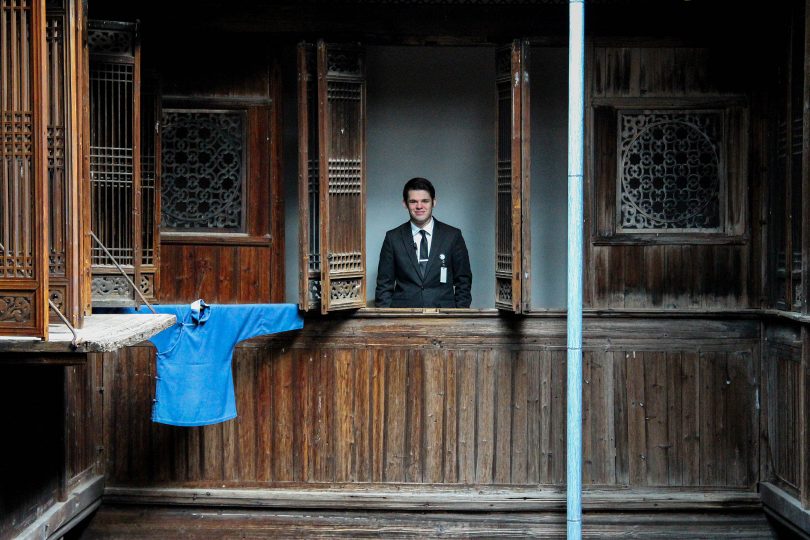

Dave D’Entremont could not agree more. He first saw Yin Yu Tang when he visited the house in 2003 and now works as a guest service representative leading tours at the Peabody Essex Museum.

“There is not much change from 2003,” D’Entremont said. “We have people who know the architecture extremely well to watch the house. Every object is accounted for every morning.”

Yin Yu Tang is about 2,500 square feet including the interior courtyard but not the three kitchens. The house has two stories, comprising 16 bedrooms, one storage space and a reception hall on each floor.

D’Entremont’s favorite part about Yin Yu Tang is the first-floor reception hall where the portraits of Huang’s ancestors used to be worshipped and are still hung. The bedrooms have intricately carved lattice windows that look out onto two goldfish pools in the central courtyard. There is a wooden partition behind the entrance which D’Entremont explained is designed to keep evil spirits from entering.

“Do you see the swastikas and shapes of vases in the lattice?” D’Entremont asked. “Vase is pronounced as ‘Ping’ in Chinese. It suggests harmony and peace.”

Yin Yu Tang was mainly constructed with wood through mortise and tenon joints, new nails were used. D’Entremont said 70 percent of the household objects, such as cookers and posters originally came with the house. An elevator was built for wheelchair accessibility later.

Yin Yu Tang is available for scheduled self-guided, audio and docent-led tours. The number of guests in the house is limited to 25 at any given 30 minutes. D’Entremont said this practice can help preserve the house, as there can be more than 2,000 visitors in the museum on weekends and holidays.

Shihao Hu, a Boston College student from China, said Yin Yu Tang reminds him of traditional architecture in his hometown of Zhejiang, a neighboring province to Anhui.

“It feels like living in the 1980s,” Hu said. “It is my first time seeing a complete Chinese house in the U.S. and it looks well-preserved. Normally, Chinese exhibits are collections of art works like porcelains or antiques.”

Along with Chinese visitors, many relate themselves to Yin Yu Tang. Carlos Morales said the house reminded him of his home in Mexico City.

“There are over 20 of my family members living in a house like this but ours are a lot bigger,” Carlos said. “I like the goldfish ponds. We don’t have that.”

Despite the popularity of Yin Yu Tang at the Peabody Essex Museum, Zhen Li, an architecture professor at Tongji University in China, has a different opinion about the move. Li and his team were given a UNESCO Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Protection of Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region for a series of projects in ancient towns in China in 2003.

“Overall I don’t agree on the method of moving historical buildings, especially for long distance,” Li said. “It would only be the last resort, like when a dam or metro line is under construction. Although Yin Yu Tang can be reassembled well in the U.S., it eventually lost its ‘block links,’ such as Hui merchants culture and the endemic environment. It can turn [into a] business trade if the method is promoted.”

Li thinks transporting historical buildings like Yin Yu Tang overseas would not happen now, as China’s economy rises and the sense of historical architecture protection strengthens.