By Flaviana Sandoval

BU News Service

Oscar Olivares never planned to draw the wave of anti-government protests that shook Venezuela from April to August 2017. But when his close friend, Juan Pablo Pernalete, died after being hit in the chest by a tear-gas bomb launched by government forces, Olivares felt the need to pay homage to the young Venezuelans who were turning to the streets to protest.

“It was not a decision. It was a necessity,” says Olivares. “I wanted to draw something that could help bring comfort to his parents.”

Olivares’s drawing of Juan Pablo Pernalete was the first of a series that portrayed young Venezuelans who lost their lives in the 2017 protests.

“To think that their families were going through the same we went through with Juan made me feel those deaths very deeply and closely and made me have an unwanted need to pay homage to them, too,” Olivares said.

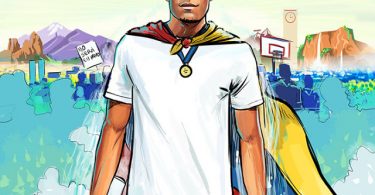

The drawings were widely shared and liked on social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram. One of the drawings, “Heroes de la Libertad” (Heroes of Liberty), depicted over 60 young protesters who died as a result of government forces’ repression. This painting had a tremendous success amongst the public, both in Venezuela and abroad. Olivares’s only wish is that his work can serve as a tribute to “remember the young Venezuelans who lost their lives fighting for a better country.”

Olivares is one of many Venezuelan artists who, in the midst of an economic and political crisis, have decided to use their work to call for peace, contribute to building a better society and bring hope to Venezuelans.

“Despite the ongoing crisis that has caused many artistic institutions and museums to close or decay, I feel that people, and especially young people in Venezuela, are uniting to create new spaces to show what is being done,” said Flix, an urban Venezuelan street artist currently working in Lisbon, Portugal.

Flix uses a pseudonym because most of his interventions on the streets of Caracas, Venezuela’s capital city, were not authorized by the government. He started his career with small interventions like stickers and posters that he placed in public spaces to “break the monotony with a twist of color and geometry.” He later participated in urban space restoration projects promoted by municipal governments in Caracas.

His most notorious intervention was at the amphitheater El Hatillo, where he painted the grandstands with a colorful geometric composition.

“My intention is to contribute with elements that can make the urban space more livable and enjoyable,” Flix says. “In the middle of the chaos that is the city, and the fear people live with, I want them to find things that can make them think and reflect on life. I want to help with ideas and positive actions to counter the country’s hard situation.”

Venezuela had one of the most powerful artistic movements in Latin America in the 21st century, with prominent artists such as Carlos Cruz Diez and Jesús Soto — main representatives of the country’s famous kinetic movement — or Félix Perdomo, whose artistic work reached important venues in Switzerland, Colombia, Ecuador and even the Philbrook Museum of Art in Oklahoma.

But the ongoing economic crisis, combined with an aggressive strategy by the Venezuelan government to take control of the country’s most traditional artistic institutions and academies, has reduced the general public’s access to art and imposed hard conditions for artists to develop their work.

Many have been forced to leave Venezuela in search of better places to exercise their art.

“The positive side of what is happening now is that many people share a common goal: to preserve what is left, to maintain that artistic strength Venezuela has always had,” Flix said. “There is always going to be that positive energy and the new generations are decided to not let that potential waste away. There is still that common intention.”

Musicians in Venezuela have also been vocal about the country’s crisis. Well-known personalities like pianist Gabriela Montero have denounced the government’s authoritarian actions and human rights violations.

Most recently, famous Venezuelan orchestra conductor Gustavo Dudamel expressed his concern for the state of democracy in Venezuela and called on the government to take action to solve the humanitarian crisis caused by food and medicine shortages.

In the context of the crisis, many music groups and artists have emerged, out of the need of expressing the people’s dissatisfaction.

That was the case for Zombies No, a Venezuelan rock-punk group born in 2010. The band is “committed to speak up about the things that affect us, starting by criticizing the government, and promoting ideals of common well-being, social awareness and freedom of speech,” said Marie France Sabiani, the only female member of the group.

The band is now based in Paris but maintains a deep connection with Venezuela and its current problems.

“We recently launched our last album called ‘Divided We Fall,’ both in France and in Venezuela, through Humano Derecho Records,” Sabiani said. “We even collaborated with the NGO Fundacion Colibrí to give away our CDs in exchange for medicine donations for the pediatric hospital J.M. de los Ríos, in Caracas.”

For Zombies No, music has acquired a special relevance as a means of expression for the Venezuelan people. Despite the crisis, they see a movement in progress.

“There are many groups that have taken the initiative of protesting through their music and are promoting it as a kind of social service,” Sabiani said.“We foresee that an important wave of music will mark Venezuela’s musical history in the years to come, and it will surely create conscience.”