By Ying Wang

BU News Service

BOSTON — After working at CNN’s Beijing bureau for two years, Lu Shen was faced with confusion about her future.

Shen, an undergraduate at the University of Iowa, loved journalism but she also knew she had two realities to choose from: China’s media censorship or the uphill climb she would face if she returned to the United States to study journalism and look for a job.

Despite uncertainty, she took the plunge, attending the journalism graduate program at Northwestern University. After graduating, Shen got a job in personal finance reporting in New York, but she still remains uncertain as she seeks an H-1B work visa.

“It’s embarrassing that you find yourself in a no-win situation in China or in the U.S.,” Shen said. “I don’t think I will work in journalism if I have to go back to China.”

According to the Institute of International Education, communication and journalism students make up almost two percent of the over one million international students studying in the U.S. in the 2016-2017 academic year. China is the largest source of international students at U.S. colleges, sending 350,755 in the last academic year.

Boston’s colleges and universities are magnets for these students, but a survey of 22 Chinese graduate journalism students at Boston University, Northeastern University and Emerson College found many of these students have lingering doubts about their choice to return to the U.S. and about their futures.

The survey found that 91 percent of the students are not confident about getting the job they want in the United States and half said they had negative opinions on current journalism jobs in China.

Nine percent of the respondents said they plan to settle in the U.S. following graduation. Over half said they would return to China, either immediately or after working in the United States for a few years. Another 32 percent said they had no preference.

Survey participants said their main reasons for choosing the U.S. for journalism were the “reputation for education,” “the freedom of American press,” “diversity” and “advanced journalism skills.”

For most of those surveyed, it comes down to the tough choice of competing with American peers in the U.S. job market or returning home to work under restrictive Chinese censorship with newly acquired sensibilities about the importance of a free press.

“I don’t have a sense of belonging here,” said Yuan Tian, a Northeastern journalism graduate student from China. “I’ve simply taken America as the platform for higher education since my freshman year.”

Tian graduated from University of Oregon in 2017 with dreams of working as a TV journalist doing international reporting in her hometown of Shenzhen in China. She said she never expected to change society as a journalist.

“I think I’m going to enjoy working in China,” Tian said. “I’m not an advocate.”

Most of the students surveyed had mixed feelings about Chinese government censorship of the media. While half of the responders held a neutral attitude, 36 percent said they oppose restrictions but felt they won’t be able to improve the situation. Only nine percent thought they may be able to affect change in their country.

Hao Liu, a second-year journalism graduate student at BU, was among those with mixed feelings on censorship.

“It’s good to close accounts full of violent or sexual content, but I wouldn’t agree if dissidents or human rights activists were blocked under the censorship,” Liu said.

He said that censorship is one of major reasons motivating him to stay in the U.S. after graduation.

In January 2017, the Chinese government launched a 14-month campaign against unauthorized Internet connections, including Virtual Private Network (VPN) services that redirect users to offshore servers for access to websites such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and The New York Times, all of which are blocked in China.

This year, Apple removed VPN apps and Skype from Apple Stores in China under the government’s regulation. The tool that the Chinese government uses to censor Internet content is called Fang Huo Qiang, or “Great Firewall.”

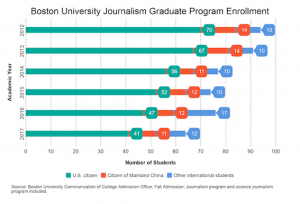

Survey of Chinese graduate students enrolled in Boston University as of December 2017. Graph by Ying Wang/ BU News Service.

Chinese students represent 17 percent of the graduate program at BU, according to the BU admissions. Similar enrollment at Emerson shows 10 percent of graduate students to be Chinese, according to the Emerson registrar’s office.

At Northeastern University’s School of Journalism, Chinese graduate students represent nearly half the students in the journalism program.

The survey found 46 percent of the particpating students in these three schools think the number of Chinese students in their programs is perfect, while 41 percent think there are too many.

As some students ready themselves for careers in China, a veteran Chinese journalist participating in the Elizabeth Neuffer fellowship at MIT said she has no intention of returning to China.

Jiajia Li was a television journalist for 10 years at Guangdong Satellite TV where she interviewed celebrities and human rights activists before resigning from her position.

“It happened many times that your pitches related to sensitive topics didn’t get approved,” Li said. “You were called to stop on the way, running to a scene or coming back from a scene, and programs could still get taken offline after the broadcast.”

Li said she thought she would be able to adapt to or even improve Chinese journalism five years ago, but failed.

“I’m pessimistic about Chinese journalism, but it was rewarding to be a close witness of China’s change in the past 10 years and share stories with the public,” she said.

Li plans to continue her “free life” as a freelancer in the United States, Hong Kong or Singapore.

“Journalists should never breach the bottom line in their hearts,” Li said. “There is no perfect journalism system in the world, just like no water has complete purity, yet you still always attempt to get the relatively [purer] water.”