By Savanna Tavakoli

BU News Service

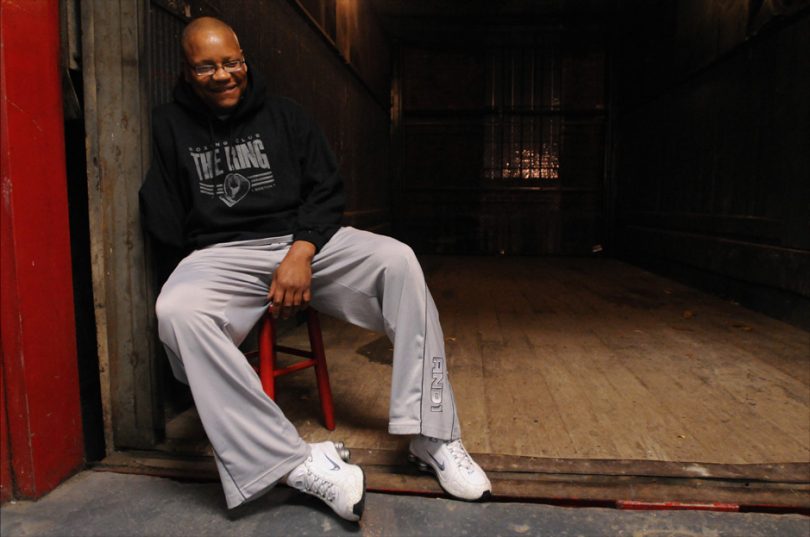

Jeffrey Leggett walked into The Ring, the Fenway boxing gym where he coaches, singing an off-key rendition of “I Put A Spell On You” and pulled a brownie out of his pocket, but quickly puts it away once he sees a Nutella crepe at the reception desk. He was wearing a navy-colored hoodie that only partially disguised his most unique feature—Leggett only has one arm.

In The Ring, where the air is thick with sweat and the sounds of fists on punching bags resonate throughout the room, Leggett, called ‘Lefty’ by his friends, is known as one of the toughest boxing coaches in the gym.

“He’s a guy that you want on your side in a fight and in life,” said Will Oberman, a boxer at The Ring. “Sometimes it’s hard when Jeff is giving you advice to tell if he’s talking about boxing or life.”

Leggett lost his right arm in 2006 when he was struck by a train during an afternoon run. By then, he’d been a boxer for 22 years, but the loss of his arm set him on a course that led him to the Ring—and his life as coach.

Now 51 years old, he never planned on being a boxer. In fact, it wasn’t until he was 19 that he first stepped into a boxing gym.

Leggett was 13 he when he moved from North Carolina to live with his uncle in Boston. His mother had just passed away and he had never known his father.

“I took it hard,” Leggett said. “I didn’t have friends growing up besides my mom and the kids I played basketball with.”

Leggett and his mother had spent their weekends in their Sunday best at the old Charleston church near their home. After his mother’s passing, however, Leggett renounced religion.

“When I got older, I left the church and lived my life, but living my life got me into more trouble,” he said. “I got into the mode where I didn’t care”

It wasn’t long after Leggett relocated to Boston that he joined a Dorchester street gang and was introduced to drugs and alcohol.

“I put myself around people who were superficial and just wanted to take advantage of me,” Leggett said. “They just wanted to take, take, take, but I didn’t see that because I didn’t think anyone could do no wrong.”

What began as recreational drug use transformed into a full-blown addiction. By 19, Leggett had turned to mugging strangers to fund his drug habit.

His gang had taken to fighting in the streets for entertainment and Leggett quickly became familiar with spending the night in a prison cell.

“At the time, if you got locked up, you were cool,” Leggett said. “I wanted to be cool. I wanted to fit in.”

Despite his experience in street fighting, Leggett’s uncle remained doubtful of his nephew’s tough persona. While the two were watching a boxing match on TV one afternoon, Leggett’s uncle bet him that he wouldn’t last in a boxing ring.

Thinking that learning boxing would lead to more wins in future street fights and earn him street cred, Leggett agreed to start training as a boxer.

“I started boxing just so I could get more experience to hang out with my friends,” Leggett said. “I went to the gym and they put a lady in front of me. She did an axe kick and the next thing I remember is I woke up on my front step.”

Determined and humiliated, Leggett returned to the gym the following day and asked one of the trainers to teach him how to knock someone out.

After a week of training, Leggett returned to the streets and used his training as a means to get more money to feed his addictions.

“I started punching cab drivers, stealing their money, and dragging them out of their windows,” Leggett said. “I was mad at myself because that wasn’t how my momma raised me but I didn’t know how to get out.”

Leggett continued to spend his nights fighting on the streets but began dedicating his days to boxing. It wasn’t until a scout who had been visiting the gym where Leggett trained offered him an opportunity to move to San Diego, California, to train professionally that Leggett decided to get sober.

“I invited my friend Rodney [Toney] who was also doing things that weren’t good for his health,” Leggett said. “I called him and I was like, ‘Yo, Rodney. I got this opportunity for us to get up out of here. Wanna come? Please come.’”

Toney agreed and the two of them began training together in California.

“We were in it together, me and Jeffrey,” said Toney. “We were up in the gym training together almost every day.”

Three months after the move, Leggett accepted an offer as Terry Norris’ sparring partner. Norris, a three-time world champion, would train with Leggett between matches.

Despite working without an agent or sponsorship, Leggett won his first seven professional matches by knocking his opponents out, a skill that beginners rarely possess.

Six months after moving to San Diego, Leggett was hit in the eye during a match. His doctor informed him that he had suffered a detached retina, an injury which ended his professional boxing career.

“I was embarrassed to come back home because I felt like a failure,” said Leggett. “I couldn’t stay in California, but I didn’t want my friends back home to know I didn’t make it.”

After earning enough money for a flight home, Leggett returned to Boston and took a job as a cook at Boston University’s Agganis Arena.

It was while he was working at the arena that he met his ex-girlfriend on the way back from his lunch break. Leggett declined to reveal the woman’s name but described her as shy and beautiful.

Although he had a girlfriend at the time, Leggett began pursuing a serious relationship with the woman he had met on his lunch break.

“She had a daughter by another man and I had a son by a woman I didn’t even know if I loved,” Leggett said. “When my new girl told me she was moving to Canada with her daughter, I decided to go with them.”

While his girlfriend took courses at a local university, Leggett looked after her daughter and began teaching boxing lessons at the YMCA.

“It felt great to get back in a ring. I was helping people better their craft,” said Leggett.

The couple lived in Toronto for almost six months before leaving for Kingston, a suburb of Ontario, in November of 2006.

“We were helping her mother move to Ontario and the last day we were there, I went jogging,” Leggett said. “My girl had told me to wait until she got out of the shower so we could walk around the park together.”

Leggett waited until his girlfriend got in the shower to sneak out of her mother’s house to go jogging on his own.

As Leggett was running, he began making his way across a set of train tracks he had come across, not seeing the incoming train.

The train had no time to stop and struck Leggett as he was running across the tracks.

“The engineer backed up the train and came over,” Leggett said. “I told him to let me get up, that I was fine, but he made me lay there until the paramedics came.”

Leggett was taken to the hospital but doesn’t remember anything after that. The doctors put him in a medically-induced coma for six days while they operated on his injuries.

“I woke up and I saw my girl and her mom and all my sisters and my nieces and nephews and I thought, ‘if I’m in heaven I’m glad I got someone I know,” Leggett said.

After temporarily losing all recollection of the incident, Leggett was told that the doctors hadn’t been able to save his arm and were forced to amputate the extremity.

“That took me to another round of destructive thinking,” said Leggett. “I hated all Canadians, people, doctors. It was an anger like when I lost my mother. And then I got better. And then I lost my career and I got pissed off. And I lose my arm. I told God, ‘look I don’t know how much more I can take. This is ridiculous.’”

Leggett spent the next month receiving medical treatment in Canada. Once he was cleared for discharge, Leggett left his girlfriend and returned to Boston for the remainder of his treatment.

“When I got back home and was in the hospital, my aunt gave me a bible and I didn’t have nothing but time so I started reading,” Leggett said. “I was reminded of my roots in North Carolina and I got back to my foundation with God.”

When Leggett was told he could leave in-patient treatment he began looking for work in Boston. He was still in rehabilitation for his amputation when he saw The Ring on Commonwealth Avenue.

“I came in here just to peek,” Leggett said, sitting in the back office of The Ring, old equipment stacked in the corner. “I told myself I would never go into another boxing ring again because I lost. I lose everything.”

As Leggett was looking around the gym, a boxer approached him and asked for help with his right hook.

“It’s hard for me to train someone to do something I was so passionate about when the rug was taken from under me,” Leggett said.

Reluctantly, Leggett agreed to train the man but refused to accept his money.

“I was just doing it casually. I didn’t walk in wanting to train anybody,” Leggett said. “The owner came up to me after a couple days and offered me a job as a trainer. I still don’t know why I said yes at the time, but I’m glad I did.”

As Leggett started to teach classes, he began growing a dedicated following of ambitious boxers who were eager to learn from him.

Because he was only working part-time at The Ring, Leggett enrolled in the counseling program at the University of Massachusetts, Boston and began volunteering with people who have endured various surgical amputations.

“Everyone’s got a story,” Leggett said. “My story helps people.”

Until 2016, Leggett worked as a counselor for children prone to gang violence, patients who had amputation surgeries, and former addicts.

“I was a counselor for a long time, but I had to take a break this year to work out my own issues,” Leggett said. “A sick man can’t help another sick man.”

Since taking a break from counseling, Leggett now works full-time as a trainer at The Ring.

“There have been times when things have been really chaotic here or falling apart but then when he comes in he has this aura of everything being alright,” Owen Cluer, the receptionist at The Ring said. “‘Jeff’s here, we’ll figure it out.’”