When as a child, you picked your dominant hand – the one that you use to write, color and play sports – you were participating in a developmental mechanism that has been working since the dawn of the human species. However, hand dominance isn’t just a characteristic for our species. Apes also have a preferred hand, although they are evenly split between lefties and righties — whereas humans are roughly 90% right-handed. As apes are our closest living relative, they serve as a comparison when looking at traits that define humanity. If we assume that the common ancestor we share with apes also had a handedness percentage of fifty-fifty, how did our percentage get so skewed in favor of right-handed individuals? One answer could be that we developed complex language, which may go with hand dominance.

The origins of human hand dominance have been a moving target for years. Since there are no living ancient humans to observe, it’s not easy to determine which hand they preferred. One way to try to find hand dominance is to go back through the fossil record, and compare arm structure. The side with the preferred hand would be ever-so-slightly larger, and show more areas on the bone for muscle attachment. However, anthropologists rarely find complete arms; and those that they do find are damaged due to weather, or wear and tear. Researchers have had to find a way around this; and one way is to look at ancient teeth.

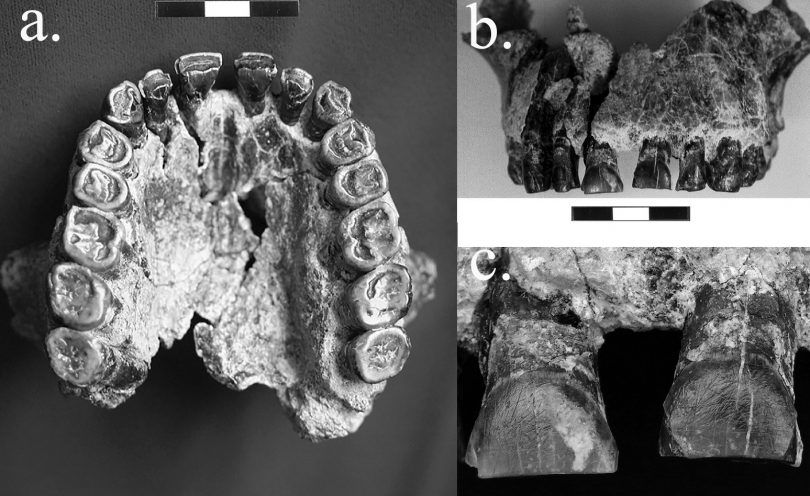

Teeth can tell us more about ancient human ancestors than what they ate, or how old they lived to be. A research team led by Dr. David Frayer of the University of Kansas may have the solved mystery of the origin of handedness by looking at 1.8 million year-old teeth. They found some mysterious marks on an upper jaw from Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, the most famous archaeological site for human origins. Looking at scratches found on the teeth, Frayer and his team determined that this individual was right-handed. This individual was a member of the species Homo habilis, the oldest human ancestor in the same genus as modern humans. H. habilis, affectionately called “handy man” by anthropologists, lived in Africa from 2.4 to 1.4 million years ago, and used primitive stone tools to make prehistoric life just a little bit easier. Their results were published in a paper in October 2016 in the Journal of Human Evolution.

The specific jaw that Frayer’s team looked at belonged to the 65th H. habilis individual found at Olduvai. During its lifetime, this individual struck its teeth with a stone tool while trying to saw off pieces of food it had clenched in its mouth. These repeated strikes left marks on the teeth, which the research team used to determine the earliest evidence for human handedness.

“Sometimes you get faint striations related to the kinds of foods that you’re eating, like if there’s grit in them” says Frayer. But these striations were larger, he said, and were likely caused by a primitive tool. Frayer hypothesized that when processing food, Homo habilis would grip whatever it was eating — whether it was meat or plant material -in its left hand, chomp down with its teeth, holding the food in place. Then it would use a stone tool to hack off pieces of food.

Frayer found marks from the stone tools on the six front teeth – the four incisors and two canines – on the upper jaw. The marks couldn’t have been on the molars or premolars, for good reason.

“You couldn’t process something back there anyway, at least not very well; you’d cut your cheek off” said Frayer. By counting up the number of marks that either leaned left, right, or straight up and down, the research team could determine which hand the Homo habilis individual was using to hold the stone tool. A vast majority of the scratches were leaning towards the individual’s left, which could have only showed up if H. habilis had been using its right hand. The majority of these scratches were grouped on the four teeth towards the right side of the mouth; which also would have happened if this individual was right-handed. This is the first time that a research team has tried to determine handedness for an ancient human ancestor. Scientists will need to look at more H. habilis individuals to see if their handedness percentage matches our own, in order to have a larger sample and draw the correct conclusion.

Another research team ran an experiment to see if these marks were actually caused by stone tools. Volunteers put on mouth guards, and were told to either pull something placed in their mouth with their right or left hand, while cutting with the opposite hand. These volunteers produced marks on their mouth guards that matched the ones found on the ancient H. habilis teeth, showing that these ancient marks were likely caused by tools.

Some scientists challenge these findings, arguing that since these marks don’t show up later in the fossil record, they must be caused by something else. While scientists find deep scratches on Neanderthal teeth, they don’t find such scratches in more modern humans, including Aborigines from Australia. Frayer theorizes that as humans developed more accurate stone tools, and moved from stone to metal, the need to use our mouths as a third hand decreased. This could account for more modern populations not having thee deep scratches in their teeth.

This research has a tie to language development as well. The left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, and also happens to house the language centers. “If they are right-handed, that implies that there is brain lateralization, where the left side of the brain is larger,” says Dr. Kristin Young of the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. A larger left hemisphere could also mean more active language centers, which could explain just how humans were able to develop language in the first place. Creating stone tools is a social experience, and teaching others the best method of creating stone tools is far easier when you can tell them exactly how to make it. In this sense handedness and language have an undeniable connection, and the origin of language could be far earlier than previously thought.